Dr Dibyesh Anand, Professor and Head of Department, International Relations, University of Westminster, argues that Prof Dawa Norbu was not just a Tibetan intellectual but also an intellectual about Tibet and more than that one of the rarest of scholars who moved beyond his identity in his work without giving up his identity and who dealt with the dominant discourse without being dictated by the dominant discourse while discussing his contribution on the subject of Third World Nationalism. He wonders why Dawa Norbu did not discuss Tibet in his Third World Nationalism discourse and offers his own understanding of it.

This article appeared in the Special Issue 2018 edition of the Tibetan Review, published in association with the JNU Tibet Forum. Excerpt from the 2nd annual symposium in memory of Prof. Dawa Norbu organized on April 7, 2016.

‘China, Tibet and world politics’, as you can imagine, is a vast subject; it covers everything in the world. So we can’t cover all of it but hopefully some aspect of it. What I want to focus on is – more specifically because this is a symposium in honour of Professor Dawa Norbu – how his ideas inspired me and how they are important in understanding China, Tibet and world politics.

I personally met him, I think, in 1999 or 2000. I was at that time pursuing my PhD on ‘Geopolitical Exotica: Tibet in Western Imagination’. If there is any other scholar with whom I have certain commonality, in terms of how we think, it would be him.

In one context Dawa Norbu is a Tibetan intellectual; but he is also an intellectual about Tibet. But for me he was more than both. His book on ‘Culture and the Politics of Third World Nationalism’ is not read by that many people. I am particularly interested in that book because in it he hardly mentions Tibet – it covers various part of the world except Tibet. I am trying to read into this book what he would normally talk about Tibet elsewhere and I wonder why he didn’t use Tibet as an example of Third World nationalism.

I am therefore going to critically read him. This is one way to honour a great scholar like him – not only reading him but also critically reading him, including critiquing him, if required. That’s what I am really trying to do here. But for me the way he inspires me is because if you look at the kind of writings he did, he focused on security studies, identity politics, and on nationalism.

In International Relations we usually don’t talk about identity and in sociology we don’t talk about international politics. Dawa Norbu was one of the rarest of scholars who managed to do that. That’s why I think he is quite inspirational. His work moves beyond his identity. Even today, many people see him as a Tibetan intellectual. But, as one of the speakers pointed out, he was more than that. He was an intellectual who happened to be Tibetan. He also used his Tibetan-ness by critiquing and exploring Tibetan-ness and in that sense he was very good. In my view he moved beyond identity without giving up his identity and dealt with the dominant discourse without being dictated by the dominant discourse; in that case he was very much an inspiration.

He looked at the role of history, the role of contemporarity, the role of centrality of marginality. Tsering was talking about it earlier – identity, nationalism and all about that. In that context, I really think that he has inspired my work and I am sure the work of quite a few of you, and hopefully those of you doing their PhD and M Phil here. Make sure that you read him. He was the best scholar who has written about international relations including international relations of Tibet and national relations of Tibet.

Now, going back to his book, or his work, on Culture and the Politics of Third World Nationalism, the question I ask myself is, how does culture and politics play an important role in nationalism? When you study Tibet, it is very much about culture. In fact, when you try to understand the China-Tibet issue today, it is about culture and how culture plays a crucial role and how culture actively deploys as a tool of survival and a tool of resistance. We have to look at the way in which certain imagination of Tibetan culture shaped Tibetan identity.

The imagination of Tibetans as non-violent shaped political and cultural strategy of how Tibetan identity has expressed largely as non-violent. You have seen the way in which the kinds of cultural identity enable one to challenge cultural genocide, what His Holiness himself calls ‘cultural genocide’. The Tibetans are a stateless nation, whether one believes them as a nation or not.

One way to challenge statelessness within the international communities is by asserting culture. Culture is not only about shared sense of belonging – that is the dominant idea about culture – it is also a site of contestation. Until and unless we recognize culture as a site of contestation, we won’t end up in a healthy discussion of the culture of Tibet.

Normally it is understandable why the focus of culture of Tibet is largely on shared sense of belonging and being stateless. But it also needs to be acknowledged that there would be a site of contestation because there would be different people arguing what it means for them to belong to Tibet and what it means to them to talk about Tibetan culture. That has to be recognized. Culture has played a very crucial part in nationalism; without it you can’t imagine Tibetan nationalism.

In his book Prof Dawa Norbu talks about proto-nationalism, which incorporates the roles of language and faith and the egalitarian ideology. It is a mixing of traditional and modernist egalitarian ideology in Tibetan nationalism.

Dawa Norbu’s work goes beyond culture or even cultural politics, though we have to be mindful of the role of politics in shaping cultural nationalism. But the role of politics goes beyond culture.

In the case of Tibet, the reality is that it is occupied. Whether one wants to reconcile with the occupation by transforming it into genuine autonomy or one wants to challenge that occupation for independence is a different matter. No one can change the fact or challenge that we are talking about occupation … a colonial kind of occupation.

In that sense we have to look into the history of common status; we have to look into the history of geo-politics, in the way China and China excursion has been powered recently. China’s excursion has, of course, had pre-existed from the very beginning. Modern China has taken traditional ideas and modernized it and claims Tibet as a part of it.

Now some people do compare how the Qing dynasty of China also made claim over Tibet or for that matter the Yuan dynasty too. But there is a difference between the imperial control of Tibet of the traditional kind and the modernist control of Tibet. The imperial powers did not deny the Tibetan identity. Imperial control also did not mean an ever intensifying colonization. On the other hand, the modernist colonization by China under the PRC is an ever intensifying colonization. And there is a consequent shrinking of space for Tibetans and how they exert themselves.

So we need to look into and understand China’s politics and its geo-politics, and how China makes Tibet a core national interest. In 1950s, Mao was, at least in the 17-Point Agreement, much more accommodative in many senses than the genuine autonomy that the Dalai Lama is asking for today. So we have to understand changing geo-politics, changing nature of the Chinese state. We have to understand the role of India too. And the role of India could expand. You could put it in question-and-answer form, if you want to. But people in India talk about the question whether Tibet is a strategic card to be used against China.

There is also the question whether Tibet is a liability, a big liability. Tibet fits in as a liability for the suggested reason that because of it we can’t have proper relations with China. We also have to understand that most Indians remain ignorant about Tibet.

But there is also a third possible stand which acknowledges Tibetans can be immense contribution to India, not only in terms of the strategy, not only in border politics and not only in terms of SFF, the Special Frontier Force which has thousand Tibetans serving in Indian military without being paid and without pension, until recently, of what their Indian counterparts get. And they have led a renaissance, for example, at Bodh Gaya.

The Dalai Lama is the biggest soft power of India, not Narendra Modi, not Sonia Gandhi, or anyone else. The Dalai Lama is the biggest soft power of India because he goes abroad and talks about India. Those things have to be kept in mind and remain a growing discourse in India. We also have to understand the role of Nepal, how it is changing there and the role of US and others.

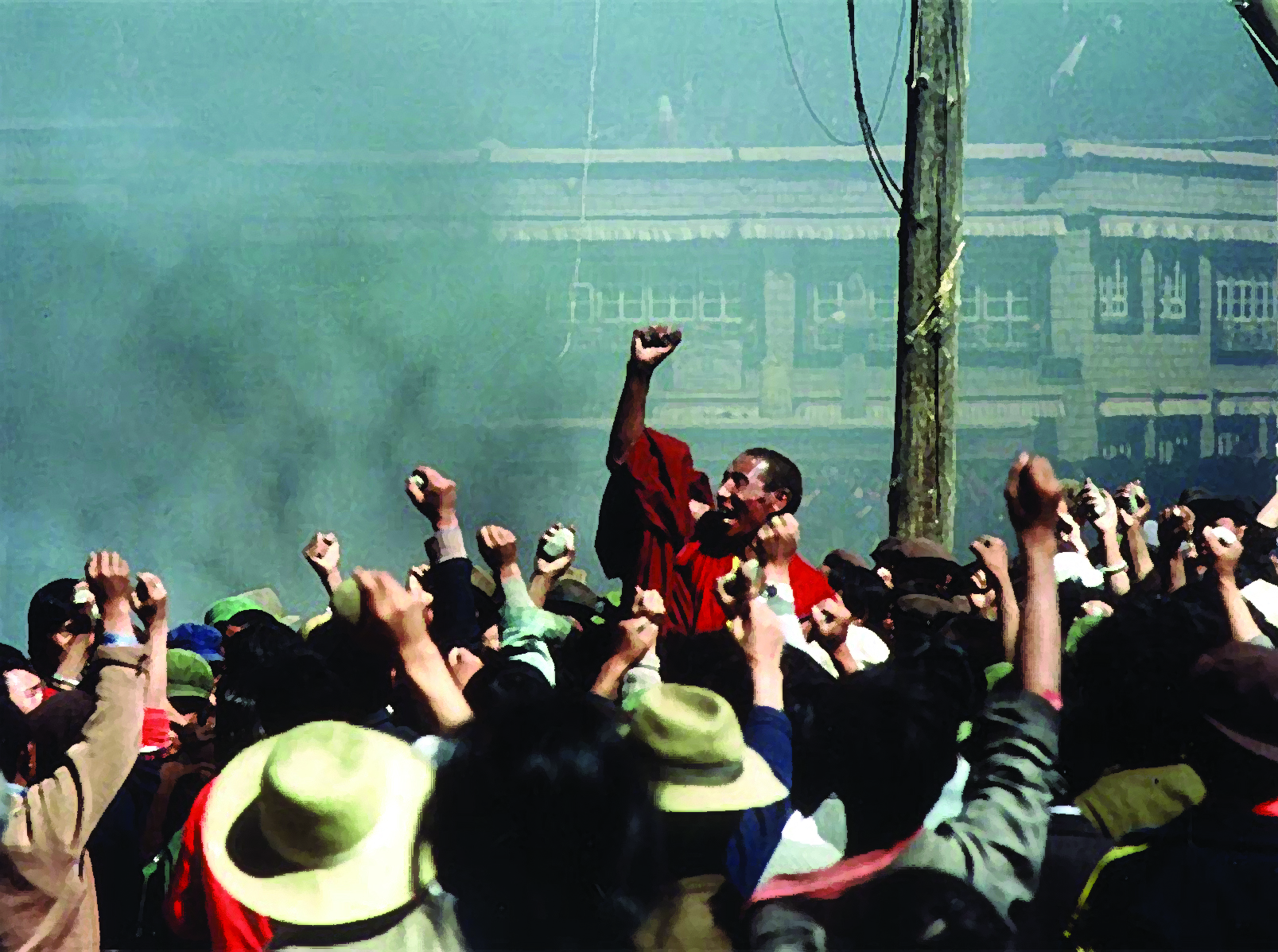

We also have to understand the context of Dawa Norbu talking about mass mobilization as being integral to nationalism. Mass mobilization is a crucial and important phenomenon because China’s authoritarian system does not allow mass mobilization. And yet masses in Tibet have mobilized themselves from time to time, be it during 1956-61 or, let’s say, 1987-89, or 2008. Mass mobilization has been part of resistance to Chinese occupation.

But mass mobilization in exile is a different phenomenon and we are entering into an odd kind of situation where some people believe that the middle way implies not talking about free Tibet. And I am even aware of people who support the middle way saying they would not chant ‘Free Tibet’ because this somehow is about independence or rangzen. So, while we are talking about Tibet, we can’t go and protest with ‘Free Tibet’. That is a very awkward position the Tibetan movement is reaching into. This we can discuss later.

And of course, one aspect – in fact I’ll summarize with that because I want to stick to the time – is reaching nationalism beyond anti-nationalism. One crucial argument that Dawa Norbu has made in his book is that in general Third World nationalism is seen in terms of anti-colonialism, and that we need to move beyond it and it goes beyond being anti-colonial. It is about tradition, and about reinventing tradition. And if we look at Tibetan nationalism, we could see those remnant arguments and also the fact that it is beyond anti-colonial.

But I would argue that this is where Dawa Norbu, if he was here today, would or might change. I don’t know whether he might change or not change when we look at Dawa Norbu’s own argument elsewhere. He finds that in the end Tibetan nationalism is anti-colonial nationalism. It is an anti-colonial nationalism which is a response to that ever intensifying colonization by China and it is a response partly to statelessness.

But the nationalism that we talk about in exile, of which most of you or many of you are part, is secondary. I won’t say it is unimportant; but it is not the most important factor. It is the nationalism we are talking of inside Tibet. Again, when we say nationalism inside Tibet, we don’t mean that it is one shape. There are people who work well within the Chinese system, who are happy with the Chinese system; and there are those who are not happy with the Chinese system but still work with it. Then there are those who are strategically using the Chinese system to transform the Chinese system as well as Tibet, and also those who resist the Chinese system. But that is part and parcel of every healthy anti-colonial nationalist movement. It is a range of responses and range of engagement that are taking place.

I would therefore argue that Third World nationalism is nothing inherently anti-colonial third world nationalism. Third World nationalism can become anti-colonial, when we look at India and Kashmir, Pakistan and Baluchistan, or Turkey and Kurdistan. And when we look at China and Tibet or Uyghur people in Xinjiang, what we find is that the so-called third world nationalism is actually anti-colonial. In that sense we see that China, in particular, is colonizing. So we need to look back and emphasize once again ways in which the so-called post colonial state, so-called Third World state are as colonial, if not more colonial, than the former colonial state in the region because they don’t even leave an inch of dignity for the people to survive, autonomous of or even independent of the so called colonial state. And in this case I am talking of Tibet.

I would read back into Culture and the Politics of Third World Nationalism of Dawa Norbu, read back colonialism into it, and argue that we need to reformulate Third World nationalism as one that could be anti-colonial but that once nation state are formed can also become potentially colonizing. In the case of Tibet and China we see it very much as a case of colonizing nationalism.

To conclude, when we say Tibet and China separately we are actually being separatist according to the Chinese context because you can’t have China and Tibet separately. I had a lecture in China’s Tibetology Research Centre when I was allowed into China in 2010. I had given the topic Tibet and China’s Public Diplomacy; that was what I was researching on at that time. They asked me to change it to ‘China’s Tibet and China’s Public Diplomacy’. I told them to go ahead with whatever change they felt was right. But in the power point presentation I had, the topic still said ‘Tibet and China’s Public Diplomacy’, so the woman in charge came in front of everyone and changed my slide to make it say ‘China’s Tibet and China’s Public Diplomacy’. This sounded ridiculous because it was a ridiculous topic.

But to me it was useful because it showed that regardless of whether the Tibetans asked for autonomy, non-autonomy, or independence, we see very clearly the way the Chinese state deals with the issue. Even when they deal with the question of how to improve governance and other things, they are very clear that none of that can challenge the Chinese role and the basic element of the colonial set up, which is an asymmetric relation of power. Tibetans and Chinese can never be equal in that set up. Tibetans can only be younger brothers who become close to the elder brother. But they can never be equal brothers and they can never ever challenge the Chinese system.

So, we have to look at things in terms of the connection of colonialism and displacement; we have to keep that in mind, recognize or at least try to understand the rule and the governance and other systems through the lens of colonization, whether it fits or not. And finally we have to recognize Tibet apart from being just a victim; as a part and parcel of the world we live in where state, or the ideas and political practices privilege nation state over people. And that, I would say, is the main feature of world politics today where the state is privileged over the people. And that, I would also argue, is the biggest tragedy of the contemporary world: that states are privileged over people.

Thank you very much!

* Transcribed and edited text