Phuntsog Wangyal

(Tibetanreview.net, May 7, 2016)

Mustang is a region of Nepal offering breathtaking scenery and vast, magnificent landscapes. Despite its tranquil beauty, this region became a vital base as a strategic site for Tibetans to establish a secret resistance camp and fight for their homeland in 1962. Amid the turmoil unfolding across the border in Tibet, it became a site of importance, and of tragedy.

Ultimately, they had to disband in 1974 under great pressure from multiple sides. When His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama asked them via a recorded message to lay down their arms and end their conflict, many chose to die rather than go against his advice. One individual even died by cutting his own throat. This article documents the life of this man, Commander Pachen, who served in the resistance camp as one of the main leaders of the struggle.

Pachen was described as “one of the five commanders” in the Mustang Tibetan Camp. There were seven regiments (Rukhag) in the camp, and all of them were led or commanded by fighters trained by the CIA in America. Pachen was not one of these commanders, but he was one of the main leaders serving in the camp from its inception. I thought some readers might wonder who this man was, and want to understand the background of his past.

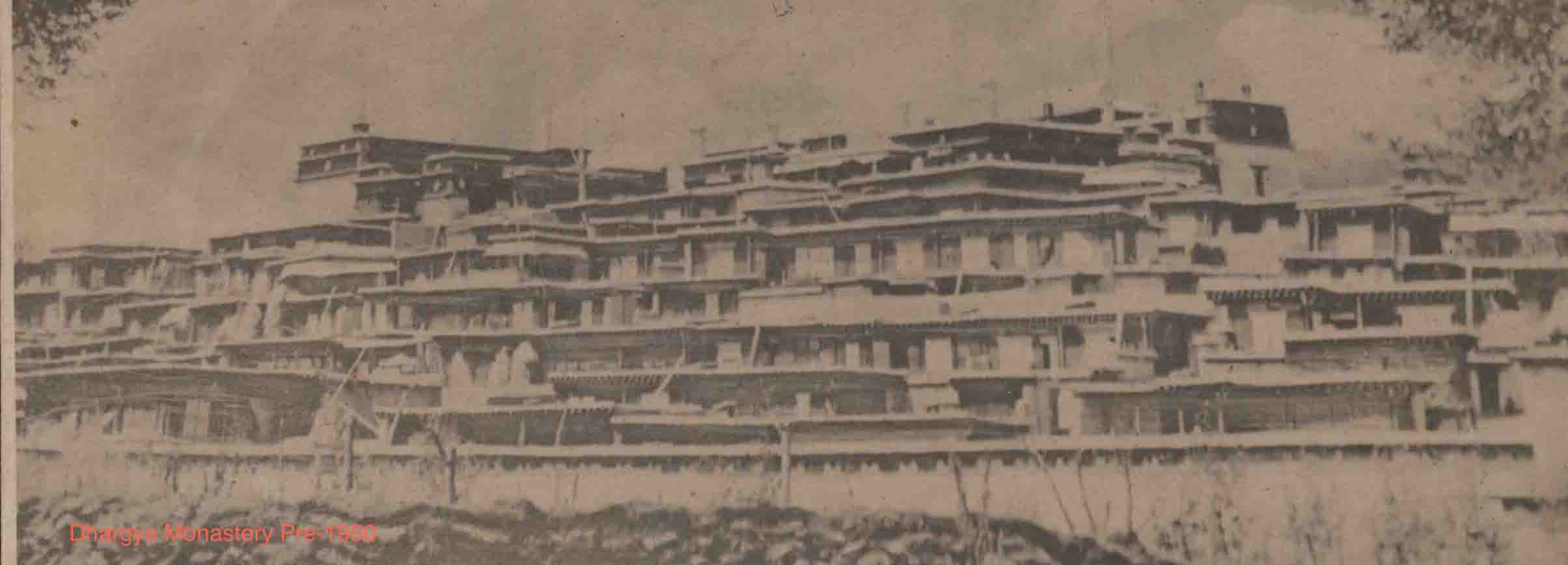

Pachen can literally be translated as “man of great courage”, and this was certainly the case for the man I knew; a true Khampa warrior. He was from a small, yet beautiful village situated near the bank of the Zachu River in Rongpatsa, Eastern Tibet, called Ge-nge. His family had a long history of serving Dhargye Gonpa, which was a leading Buddhist monastery in this region of Kham Tehor, now in Kandze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Dhargye monastery was known to have some 1,900 monks in the 1950s and it exercised enormous influence across the region. Its power was so dominant that the whole region came to be known as Tehor Dhargye, in contrast to Tehor Kandze. The monastery and its people were well known for their support to the Tibetan government in Lhasa. His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama granted a decree, recognizing Dhargye monastery as The Guardian of the East, a place at the frontier of Eastern Tibet.

Pachen’s family worked with great dedication and commitment. One of his uncles was Tengyal, who became quite renowned, and was mostly known as Akhu Tengyal – Akhu meaning paternal uncle. Akhu Tengyal fought in many battles during an earlier war known in history as the Sino-Tibetan War, which started in 1930, and he survived as a revered hero. What began as a local conflict developed into a larger war between the Lhasa government with Dhargye monastery, and Chinese Warlord Liu Wen-Hui of Sichuan Province, who later sought assistance from Qinghai Province. The combined forces defeated the Tibetans and Dhargye monastery was burned to ashes for a second time. The war ended in 1932 after a peace agreement was signed, drawing Tibet’s eastern border at the Yangze River.

In 1958 Akhu Tengyal’s nephew Pachen was still a young monk holding an important position (Choe-nyer) in Dhargye monastery. In that year, during the holy month of Saga Dawa (the anniversary of Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and passing on the fifteenth day of the fourth month according to the Tibetan calendar), the year of the Male Earth Dog, a large congregation of monks gathered in Dhargye monastery. The resident monks chanted their prayers, and tormas (cakes made of tsampa) were offered to deities and effigies, which were burned on the fire. They were aimed at dispelling the enemies of Dharma, and removing the obstacles disturbing the peace in the region. In the wake of the prayers, the tormas were left on the roof of the assembly hall for the birds, mostly ravens – believed to be birds of our local protector, Akhu Dralha. The sheer amount of tormas was so huge that rainwater passing through the streets of the surrounding monastery was filled with tsampa for several days. It was a very busy time, especially for those of us who were studying, with our focus spent needing to attend lengthy prayer sessions, in addition to our regular philosophy classes.

A month later, on the fifteenth day of the fifth month (1st of July 1958) Pachen organized and led a small resistance group of about 40 individuals, myself included. This day was chosen as auspicious for our departure from the monastery as it was Full Moon Day, the day of Amitabha – the Buddha of Boundless Light. Almost all of us gathered were from Dhargye monastery. This monastery was famous, indeed, notorious, for having warrior-monks who kept arms as well as horses in the monastery. Although this seems unorthodox, to understand this one needs to understand the general situation in the region at that time. The whole of this part of Eastern Tibet was not dissimilar to America’s Wild West in many ways. There was no effective government with an army, or police to control the population, and people were left to defend themselves. Dhargye monastery had been attacked and robbed, and some leading monks had even been taken hostage several times during its history. For this very reason, I believe that Dhargye monastery had taken it as their right to keep arms to defend themselves, similar to the adoption of the ‘right to arms’ in the American constitution.

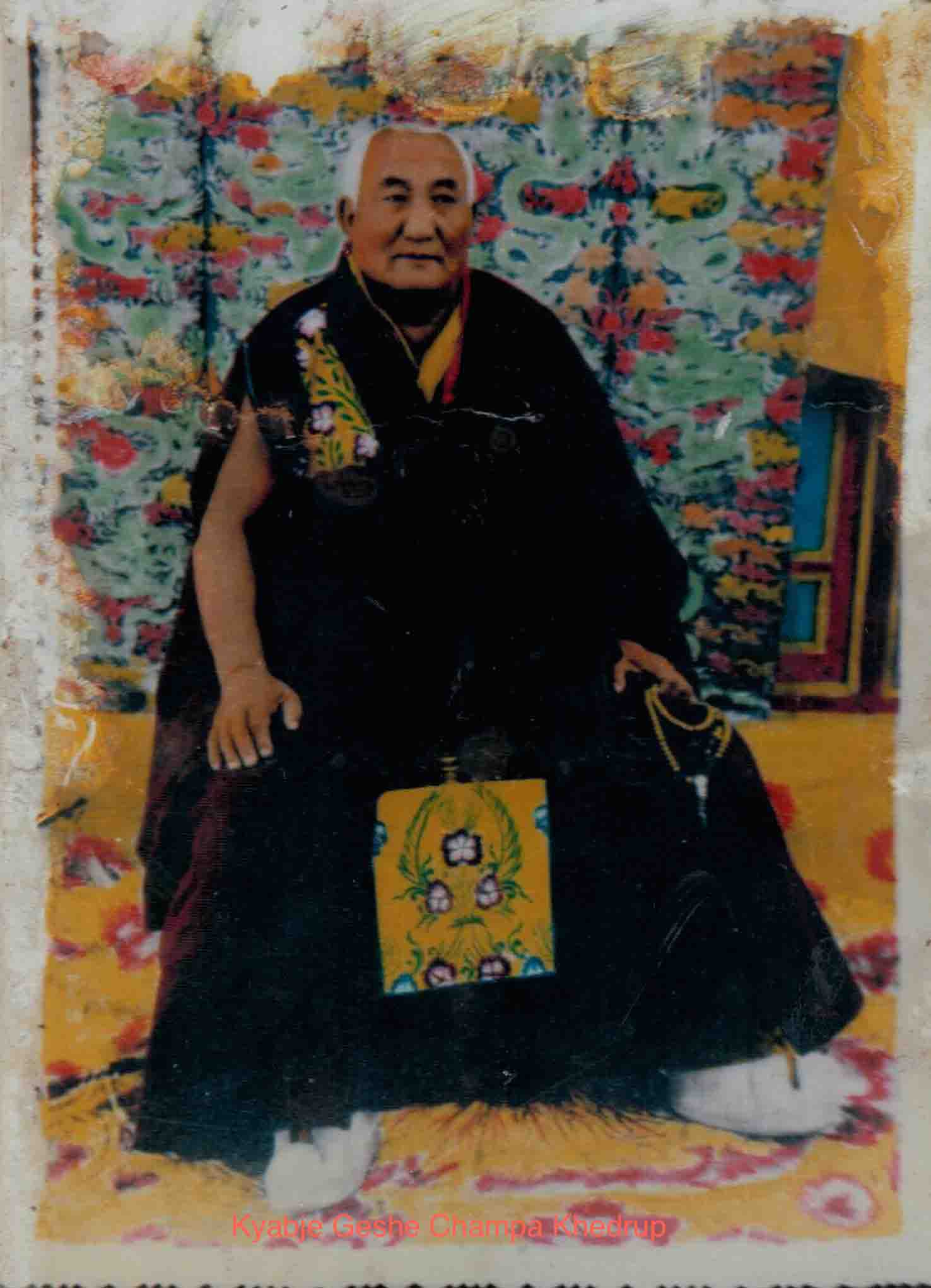

Pachen must have planned his resistance movement well in advance of that fateful night, and discussed his plans with a few chosen others. I was 16 years of age at the time. Just before we departed, I had the opportunity to consult my most revered teacher, Geshe Champa Khedrup, the head of the monastery, who later died in prison in 1961. My teacher said it was time for me to leave and not to return until I would be helpful to others. I thought he must have meant for me to go and become a learned Geshe, and to help others. In my heart I prayed that his advice would be realized in my life and that I would return to Dhargye monastery again. Unfortunately that was not to be the case. In the early 1960s Dhargye monastery was once again completely destroyed, with no remaining trace.

Pachen was already dressed in layperson’s clothes as we met at the gateway. He was to become our leader from that day on. At midnight we passed through the West gate of Dhargye monastery. I can still remember how our group was gathered in a quite disorganized manner, under the gaze of the cold blue sky which was dotted with stars. Some of us were still dressed in our monk’s robes; others armed with swords, and some even with rifles. People were shouting where we could find arms, some responded emotionally to go to Sungma Khang, the temples of wrathful deities. It was here that the weapons used as offering to the deities could be found, yet the objects were intended as religious gifts.

The stars were twinkling over our heads as if they were filled with the same nervous excitement as we were amid the narrow streets of the monastery. As we journeyed west, I remember looking back and gazing at my village – my home – and thinking of my mother who had no idea I was leaving. It happened to be the very last time I would see my village while my mother was alive. Some ten years later, when first contact between the people living inside Tibet and those in exile became possible, I learned the sad reality that my mother had died from receiving severe beatings by local officers for several months, and that one day neighbors had found her battered body in a nearby river. Such a horrible story was a regular feature of events at the time. From then on, we were deemed ‘bandits’ as the Chinese called us, and we were exposed to open confrontation from the People’s Liberation Army.

It was the time of the introduction of ‘People’s Reforms’ leading to ‘Class Struggles’, and the introduction of the Commune System; the end of private property in Kham. It was most likely that Pachen formed this resistance group to stand against the reform, and to show the people’s opposition to the new system. Tibetans enjoyed a remarkable Buddhist culture that they could be very proud of, yet socially and politically were backward at the time. Social services such as public schools to teach modern science, geography and international relations, and hospitals to provide modern medicine and basic healthcare to treat a wounded soldier were unheard of. Militarily, once a much-feared kingdom with a strong army in central Asia, Tibet degenerated so much and became so weak that any other country could have easily overrun us. Living for such a long time in total isolation from the rest of the world, Tibetans could not fully understand the power of China, and their resolve to change Tibetan society. No Tibetans at the time could visualize that they could not win against China, and that their faith, friends and neighbors would ultimately let them down.

Pachen led and commanded his men in many battles across Tibet until he died in 1974 in Mustang, Nepal. Initially he commanded our small group of volunteers from Dhargye. None of us, including Pachen himself, had any kind of military training, let alone any experience of fighting the People’s Liberation Army – who had long fought against both the Kuomintang and the Japanese armies, and were well equipped with modern Soviet weapons. Despite this, with great determination and the courage of a true Khampa warrior, Pachen fought many battles in the north, and from Kham to central Tibet. Later he joined a much larger and more organized Tibetan resistance movement in southern Tibet, composed of mostly freedom fighters from a voluntary organization called ‘Four Rivers and Six Ranges’. In this movement in southern Tibet, Pachen became one of the most formidable leaders, commanding a much larger force representing fighters from all of Dhargye area in Kham. He was feared by his opponents and highly respected by the fighters he commanded.

During these battles in Tibet, Pachen lost many of his men, including several of his relatives. His brother-in-law, Rinchen Tsephel, was killed at Tsatsa in Kham, as well as his brother Rinchen Gonpo who was killed in Wa Zong in Lhokha, and his nephew Pema Samdup in Kongpo, Southern Tibet. His sister was left behind at home in the village, called Pema Lhamo. She managed to successfully bring up her six children who in turn had families of their own. However, we discovered that she had endured unbearable suffering for something she had not done, due to her relation to Pachen. Such suffering by the families of those who joined the resistance movement was yet another tragic story of our time.

This resistance group in the south consisted of a few thousand fighters equipped with arms dropped by the American CIA from the air, and occupied most of the areas to the south of the River Kyishu, near Lhasa, stretching all the way to the Indian border near Arunachal Pradesh. The resistance managed to keep the whole area under their control without Chinese presence. This certainly provided His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and the entailing entourage a safe passage to India without being attacked and stopped by the Chinese in 1959.

In the wake of the exodus of Tibetans into exile, Pachen and a handful of those who survived from his original group of about 40 individuals, myself among them, reached the sanctuary of India. However, Pachen soon joined what was then known as a secret Tibetan or Khampa Resistance Camp, established in Mustang at around the time of Sino-India conflict which ended with the embarrassing defeat suffered by the Indian army in 1962. It was so secret that there was no significant activity of the camp reported through public media. After some ten years it became clear that all was not well at the camp, and many stories including a bitter disagreement among the leaders for and against ending the operation came to light. Pachen was known to have taken a leading role for continuing the operation, and opposed General Wangdu’s decision to end the operation. Ultimately what was then called the “Khampa Disarmament”, launched by the Nepalese government forced the camp to close in 1974.

Pachen was known to have served different positions of high responsibility in the camp, including the departments of judicial enquiries, propaganda and publicity. The greatest frustration amongst many of them was that they could not go to fight for Tibet, which was the very reason they joined the movement in the first place, and had endured such hardship in the Mustang Resistance Camp. At the time of Pachen leading his resistance group in 1958 he certainly had the hope of being able to do something to reverse the situation in Tibet, but did not have any expectation from some definite assistance to deliver success.

At the time of joining the Mustang Resistance camp it was different from what he had expected, with genial support from America. It must have been the hardest thing he and his comrades could believe that fighting for a liberated Tibet was never a part of the master plan by the Americans, who had guided and supported them. It was too late to appreciate the Tibetan saying: Hope is something we must never lose, but expectation may let you down.

It was during the time of Cold War that the American CIA found the group of Tibetan resistance fighters useful in their attempt to restrain communist China, who was then an ally of the Soviet Union. Tibetans happily accepted CIA support, genially believing that they were fighting for Tibet and not for a larger game against communism. They were sadly proven wrong when US president Richard Nixon reached an agreement with China in 1972 to end American support, pulling the plug in the CIA project which eventually contributed to the closure of the Mustang Tibetan camp.

As a teenager, I used to imagine Panchen as ‘Shenpa’, a brave hero in the story of Ling Gesar, and would feel inspired. Others at the time often compared him to ‘Denma’ of the King Gesar stories – an epic tale similar to that of the English King Arthur and the Indian Mahabharata. Gesar stories were very popular, especially among the nomads and herders in Kham. Many said this was the reason why Khampas became warriors, according to legend.

As a child boys were encouraged to read Gesar stories, and those who were illiterate learned their history through the stories passed on from elders. As young boys at a time when there were no films or television, we used to love hearing them, listening with enthralled interest. However the tradition of performing and singing the Gesar story is now slowly disappearing, and are sadly of less interest to younger generations.

Pachen was not a very tall man, he had a darker complexion than most Tibetans, and would ride a grey horse. He had a personality that made you feel safe and confident of winning every battle you fought, and at the time you never thought of losing. He was a serious man, and took his responsibility very well, being both humble and simple, yet brave and decisive, and he always led his men from the front in the battles he fought. After some sixty years I began to realize that his shortcomings, if any, were his overconfidence and high expectations from those he trusted unconditionally.

Almost at the same time Pachen ended his life, the highly publicized Mustang Tibetan Camp also ended up as a small chapter in the long bitter history of Tibet. Mustang is a beautiful land with a thriving Tibetan culture. Tibetans once fought from this land with the high hope of freedom, and sadly failed. With a deep faith in Buddhism, Tibetans would console themselves by appreciating the saying: No point in worrying if you can’t do anything, and no need to worry if you can do something.

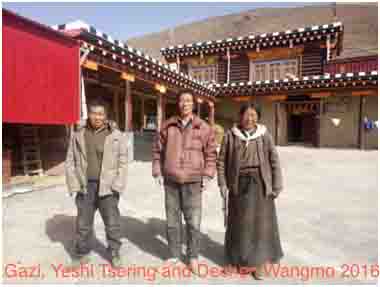

Today, some of Pachen’s many close relatives from his late sister Pema Lhamo live on as different families in Tibet. Her two sons Gazi and Yeshi Tsering, with their wife Dechen Wangmo, live in his original home in Ge-nye, recently rebuilt. Another relative is Rinchen Tenzin, who later went to India. He became a monk and studied Buddhism in Sera Monastery in south India, and has obtained a Geshe degree for his scholarship.

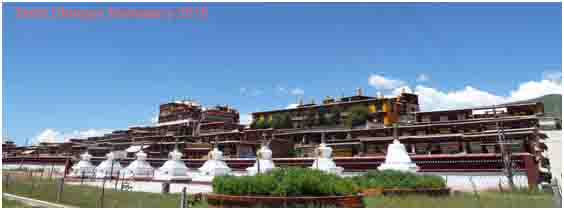

Amid a changing political situation the local government obtained permission to rebuild Dhargye monastery in June 1983. In the last 20-odd years the surviving monks, with great enthusiasm under the capable leadership of its chairman Gyalten Rinpoche and abbot Geshe Pema Samten, have rebuilt the monastery, and it now has some 230 monks with extensive Buddhist philosophy courses, and is able to provide religious services to the local population. None of this will bring back their revered hero Pachen, but the memory of their past glory and Pachen’s lifelong public service may hopefully continue amongst the younger generations.

Ultimately, none of us know exactly what was going through his mind when commander Pachen died at his own hand. What those of us who knew him can be certain of is that Pachen remains in our memory as a brave Tibetan who cared for his people and their way of life, and spent his adult life in the service of a cause that he believed was just and right – a cause he felt he could die for. He was an ordinary Khampa who proved courageous and rose to be a good leader and a brave fighter, receiving so little acknowledgement from an indifferent society.

————-

The author would like to acknowledge with thanks following individuals for their help in writing this article: Jidung la, Lobsang Tsondue, Pema Samten and Sangye Dhondup.

Photo credit: Geshab Tenzin, Lobsang Tsondue, Pema Samten.

___________________________________________________________________________

![]() Phuntsog Wangyal is a former representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in London and a founding trustee of the charity Tibet Foundation.

Phuntsog Wangyal is a former representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in London and a founding trustee of the charity Tibet Foundation.