Book Review by Tenzin Dickie*

A Home in Tibet

By Tsering Wangmo Dhompa

Penguin (New Delhi, 2013)

Pp. 320; Rs. 499

A Home in Tibet is one of the most significant works by a Tibetan writer ever.The history of secular prose literature written by Tibetans is briefly told—although the nobleman Tsering Wangyal Dokhar wrote The Tale of The Incomparable Prince in the 1700s, followed by the scholar Gedun Chophel’s travel memoir in the 1930s (recently available as Grains of Gold in a fantastic English translation by Thupten Jinpa Langri and Donald Lopez), it wasn’t until the 1980s that we saw the so-called birth of modern Tibetan literature and a full flowering of contemporary poetry and prose. I think this book is so significant because it’s such a tremendous aesthetic achievement; A Home in Tibet probably has the most gorgeously crafted sentences in a prose composition by any Tibetan writer.

There have been other memoirs written since the fall of Tibet. There was a rash of books written by former Tibetan aristocrats and some were even readable. There have been other important memoirs, including Professor Dawa Norbu’s Red Star Over Tibet and Tibet: the Road Ahead. A memoir that I particularly admired was Six Stars with a Crooked Neck, an illuminating and beautifully written personal account of the Cultural Revolution by scholar and writer Pema Bhum (superbly translated by Lauran Hartley, a scholar of modern Tibetan literature).

A Home in Tibet is the maiden prose work by Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, an accomplished and respected poet with three books and two chapbooks. It is a love story, with mother and country in the role of the beloved and as such, it is a fitting tribute to both. It’s the story of Dhompa and her mother, and an account of Dhompa’s returns back to her homeland in Tibet. Often this memoir felt like one long prose poem to me. If you are a reader who prefers a straight line from point A to B in a narrative, this book may not be for you; but if you are willing to be seduced by the beauty of sentences and to enjoy the pleasures of being on the plateau in the hands of a writer in full possession of her craft, head straight for a bookstore. But make that a bookstore in India. (The book is for sale on the subcontinent only.)

Dhompa’s poetic sensibility pervades the three hundred pages of the book. A kind of wisdom attends her passages wherever the poet takes over. She asks, “The yaks are desultory eaters: what would be the purpose of quickening their gait when the field stretches beyond their vision into eternity?” Of the land itself, she writes:

“This land makes me believe anything is possible. Here lies a gift unraveled as was meant to be: within its many folds are men, beasts, insects and grass. The green goes on and on in relentless beauty. As I look at the land I am heartbroken thinking of the future when I will not be here and when this place, too, will be something else. Here in the boundless field, with no other person in sight, I understand what it takes for a nomad to feel part of the world when he is sitting on the back of a horse measuring distance and the day’s labor by the hour.”

A favorite moment of mine comes when Dhompa asks her aunt what the date is. The aunt’s answer? The first day of the fifth lunar month, the year of the fire dog 2133. I grew up in a closed Tibetan settlement in India with elderly people for whom the only frame of reference was a Tibetan one but it has been a very long time since I knew what date it was according to the Tibetan calendar. Here is Dhompa on her late mother: “I believe still what I felt then: her love will see me through my lifetime, perhaps even a few more lifetimes.” A golden opportunity to insert a small eye-opening disquisition on that mystical Tibetan art—or is it craft—of reincarnation. I can’t see a non-Tibetan writer letting this kind of lovely, understated statement stand on its own. But for Dhompa, the powerful idea that her mother’s love will see her through a few more lifetimes is not a strange thing that needs explaining away. Incidentally, that single sentence is full of life—the line has the surface tension of poetry. As she intends, the line holds and vibrates, sending its echoes resonating through the book.

The essayist Vivian Gornick stresses the importance of knowing which self is speaking. In Dhompa’s memoir, where it’s the daughter speaking, the book soars with beauty and truth. Tsering Choden Dhompa was a remarkable woman. The daughter of a chieftain in her hometown, she married the son of a chieftain. She was set to tread the path of the women before her. Then the Chinese came, and she made the long and dangerous journey to India, to safety and exile and a new uncertain life. By that time she had left her husband, an unusual thing for a woman to do in those days. In the exile capital of Dharamsala, she brought up her daughter as a single parent while carrying on an important role in the community. She was a member of the Tibetan people’s deputies, a parliamentarian. You feel the enduring tensile strength of the bond between Dhompa and her mother vibrating throughout the book, binding its separate episodes together. She writes of their primal necessity to each other, “When there are just two of you in the world, you carry the fear that if one of the two should go, there will be just one left; you are two against the idea of time, death and happiness.”

There was just one left. The book, which is not chronological, begins with the death of Dhompa’s mother—a roadside accident on a highway in India. It’s a heartbreaking scene and Dhompa renders a world of pain in spare, unadorned prose. Years after her mother’s death, the pain lingers, as raw beneath the skin as ever: “And just like that, as it often happens with those of us who live with ageing heartaches, I think of my mother who is no more. I feel all at once, once again, the enormity of her absence.”

Even in her absence, Tsering Choden Dhompa has a full-bodied presence. In the chapters where she is living and breathing, she is such a captivating figure that all we can do is feel her loss, as a mother and as a character. I can see the symmetry in this situation—the great tragedy of Dhompa’s life is that her mother passed away. When she did not receive more time with her mother, why should the reader? As much as we mourn this wonderful and remarkable woman, I think we would mourn her even more if we were given more time with her.

There is some knowledge that Dhompa refuses the reader. Dhompa tells us her father was not the man her mother was married to. She says her mother was her father also and leaves the matter there—she won’t tell us whether she even knew who he was. Regarding Dhompa’s own life in San Francisco, there’s one glancing reference to a broken engagement, to a fiancé who was unkind, and nothing else. In her hometown in Tibet, the kids can’t tell if Dhompa is a man or a woman because her pants and her long hair, worn loose like the men in the area, confuse them. I thought the kids’ confusion highlights Dhompa’s curiously asexual state throughout the book. I wondered about the men in her life just as I wondered about the men in her mother’s life. I wondered about their secret lives.

I wondered because I cared about them, these two unusual, courageous and brilliant women. A Home in Tibet is a gorgeous composition and a major achievement by a Tibetan writer. It’s the story of exile, steeped in wandering, rootlessness and supreme loss amid the departures and returns, the disappointments and hopes, of a life lived, as exiles must, on the margins.

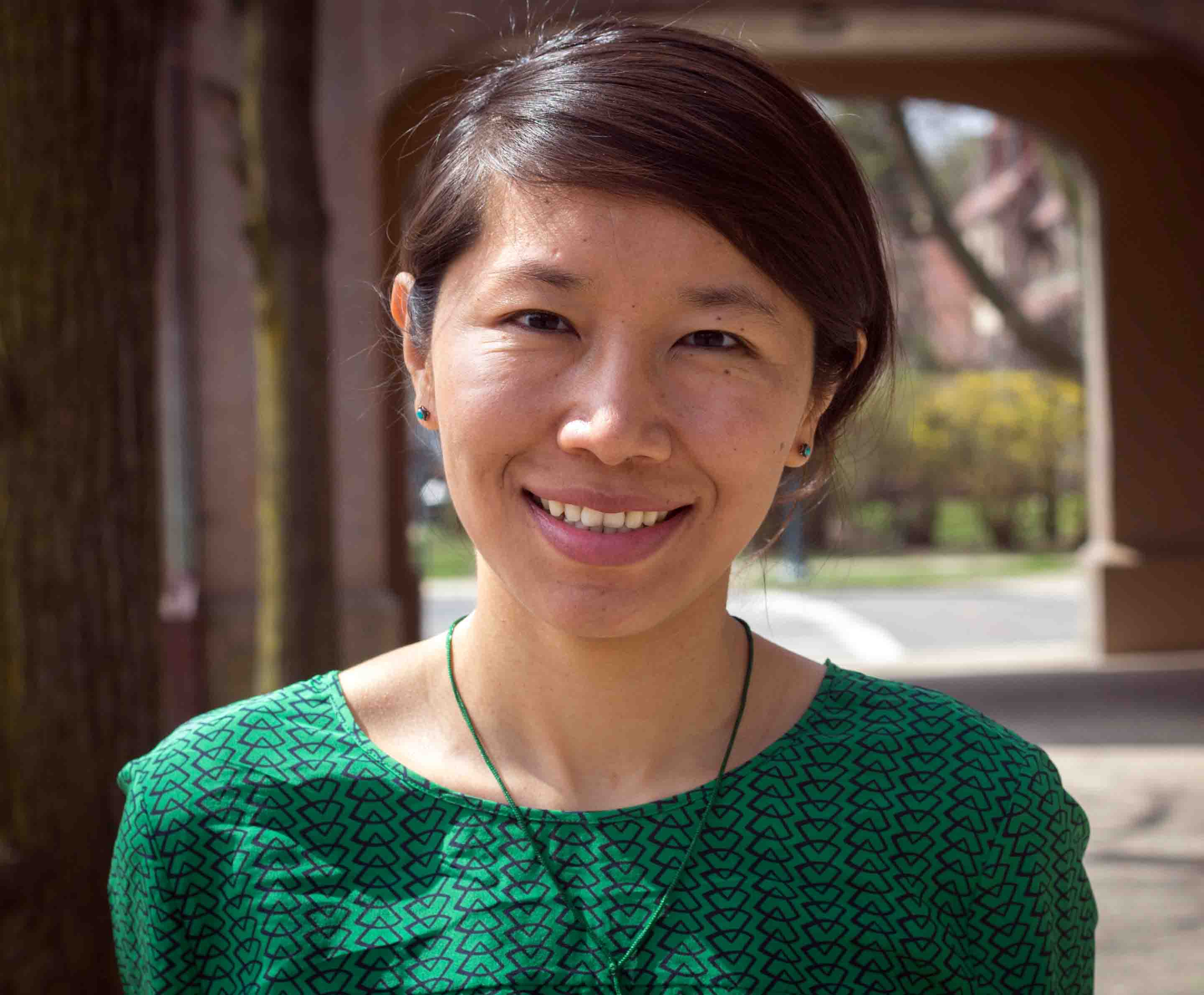

* Tenzin Dickie is a writer and translator living in New York City. She is an editor of the Treasury of Lives, a project of the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation. She is also on the editorial board of Tibetan Political Review and Tibet Web Digest. She can be contacted at td2352@columbia.edu.