The relative stability of US-China partnership has continued since 1972 and propelled China to its current position as global power while the constant bickering between the two sides through media channels has been, in the words of Chairman Mao Zedong, nothing more than the firing of “empty canons,” says Ben Byrne*

(TibetanReview.net, Feb02’21)

Modern American policy regarding China was largely forged during the Nixon (1969-74) and Reagan (1981 – 1989) administrations. President Nixon brought Beijing in from the diplomatic cold when he made his famous trip to the Chinese capital to meet Mao Zedong in 1972. Seven years later the United States and the People’s Republic of China released a joint communique formerly switching diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. It was Nixon’s strong belief that the “outstanding abilities” of the Chinese people would “propel them to world leadership.” With Reagan came the “Third Communique” of August 17, 1982. Through this, according to Nixon’s Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, China “achieved another decade of American assistance as it built its economic and military power and its capacity to play an independent role in world affairs.” President Reagan visited China himself in 1984 and, in a speech at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, hailed a relationship between the two based on “mutual respect and mutual benefit.”

Disagreements about political ideology and Taiwan often simmered through the 1970s and 80s, but the common goals of economic development and money-making formed the basis of a workable understanding, which included deals on technology transfers, tax laws and arms sales. Tibet or Xinjiang were not mentioned in any high-level discussions as this détente unfolded. By the time the Obama administration was in office, the US President was publicly stating that he “welcomed the rise of China.” As Vice President, Joe Biden travelled to China for a six day visit in 2011. He was accompanied on this tour by his then counterpart Xi Jinping. One of the goals of the visit was for the two men to form a “deep, personal relationship.” Two years later, after Xi, by then President, had proposed “a new type of great power relationship” that would essentially see the two powers sharing the Pacific theatre, US National Security Advisor Susan Rice expressed a willingness to cooperate: “When it comes to China, we seek to operationalize a new model of major power relations. That means managing inevitable competition while forging deeper cooperation on issues where our interests converge – in Asia and beyond.” When Joe Biden was elected President in November, one Chinese source was quoted saying of President Xi, “Our President must be a little relieved. He knows Biden well.”

This narrative of relative stability runs contrary to the story about US-China relations often told by the popular press. China is vilified for human rights abuse and criticized for its Communist ideology by western media. Chairman Mao Zedong referred to this constant backbiting between the US and China through media channels as the firing of “empty canons.” In dialog with Henry Kissinger in November 1973 Mao said: “So long as the objectives are the same, we would not harm you nor would you harm us…Actually it would be that sometime we want to criticize you for a while and you want to criticize us for a while. That, your president (Nixon) said, is the ideological influence. You say, “away with you Communists!” We say, “away with you imperialists!” Sometimes we say things like that.” In conversation with Chinese Prime Minister Chou En Lai in 1972, President Nixon echoed this sentiment, and spoke of the importance of designing rhetoric that would appease anti-Chinese factions within the American political scene whilst simultaneously maintaining a long-term strategic partnership.

The greatest challenge to this understanding came in 1989 with the Tiananmen Square Massacre. The American press and public were outraged at the images from Beijing that were beamed across the globe. Kissinger recalled, in the aftermath of Tiananmen “the entire Sino-US relationship…came under attack from across a wide political spectrum.” Pressure was being applied on the US government to impose tough sanctions on China, some were even calling for a US intervention to install a democratic government in Beijing. President George H.W. Bush, however, was reluctant to act. He had served as America’s de facto ambassador to China during Gerald Ford’s administration and had forged a personable relationship with Chinese Premier and Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping. He also had great admiration for the economic reforms Deng had introduced in the 1980s. Bush watered down the sanctions on China passed by the US Congress and sent Deng a personal letter, apologetic in tone, asking the Chinese leader to “remember the principals on which my young country was founded. Those principles are democracy and freedom – freedom of speech, freedom of assemblage, freedom from arbitrary authority.” Bush went on to suggest that those principals had forced his hand and that the sanctions, which included an arms embargo, “could not be avoided.” Crucially, Bush wrote: “We must not let the aftermath of the tragic recent events undermine a vital relationship patiently built up over the past seventeen years.”

Bush’s successor Bill Clinton, elected US President in 1992, opted for an aggressive human rights approach with China in his first term. He had accused President Bush of “coddling” China in the wake of the Tiananmen massacre on the campaign trail and was convinced that Communist China would soon be relegated to the history books along with its former counterparts in Eastern Europe. To force China’s hand, his administration attempted to tie China’s Most Favoured Nation status – a designation which gives sovereign states favourable trading terms with the United States and which, in China’s case, had to be renewed every year as a stipulation of the Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974 – to “dramatic” improvements in the human rights situation in China. Clinton applied pressure for two years, extending China’s MFN status by one year through executive order in 1993, but continuing to turn the screw on the Chinese. His efforts, however, met an aggressive response from Beijing. US Secretary of State Warren Christopher was rebuffed during a visit to the Chinese capital in 1994. His Chinese interlocutors made clear that China’s human rights policy was none of America’s business and pointed out that the Americans had human rights issues of their own, probably a reference to the Los Angeles riots of 1992, which had broken out after police were videotaped using excessive force in arresting and beating Rodney King, a black man that the police officers had been booking for drunk driving. Christopher’s scheduled meeting with Jiang Zemin, who had replaced Deng as China’s paramount leader, was cancelled and he returned to the United States with his tail between his legs. Soon after, Clinton buckled and quietly extended China’s MFN status without any conditions. In 1997, Jiang Zemin visited the United States for talks with Clinton. The two leaders agreed to commit their countries “to building a constructive strategic partnership oriented towards the 21st century.” Later, China was unbound from the terms of the Jackson-Vanik amendment when it became a member of the World Trade Organisation in 2001. It now enjoys the contemporary equivalent of MFN, known as permanent normal trade relations (PNTR).

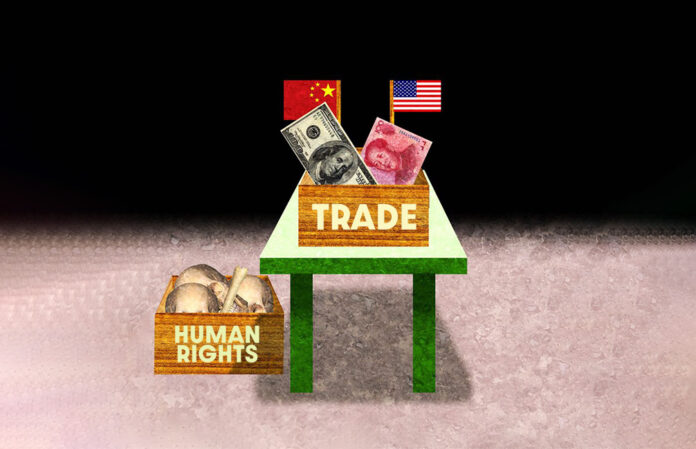

Nixon wrote to Reagan in 1982 that “the major unifying factor” that would draw the US and China closer and closer together in the coming decades could “be our economic interdependence.” This was prescient on Nixon’s part. Their interdependence has weathered Tiananmen, the suppression of the Tibetan uprising in 2008, and the reports detailing mass detention and re-education camps in Xinjiang. The fledgling Biden administration has talked tough on China, calling the actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang a genocide and inviting a Taiwanese government representative to President Biden’s inauguration. But history suggests that human rights concerns will eventually be sacrificed at the altar of economic growth and a rapprochement between the two great Pacific powers will be forthcoming.

—

* Ben Byrne has a master’s degree in History and is an independent researcher.