This editorial appeared in the Special Issue 2018 edition of the Tibetan Review.

This editorial appeared in the Special Issue 2018 edition of the Tibetan Review.

As speculations twirl around the question whether Professor Samdhong Rinpoche did or did not visit Tibet or China in November this year, unrealistic expectations about a new beginning being underway to try to resolve the issue of Tibet are being bandied about. There seems to be a refusal to learn from past experiences of false hopes raised from similar developments. The larger picture is being given a convenient slip as all sorts of recent developments seen supposedly to lend credence to a new leader with enormous new powers in China being anxious to resolve the issue of Tibet are being cited to construct an edifice of a non-existent, behind-the-scene new Sino-Tibetan bonhomie.

It bears pointing out at the very outset that China never had, and still does not have, any interest to resolve any Tibet issue. The reason is commonsensical enough. There is no relaxation – or any pointer towards it – in China’s ideology of absolute control and absolute party leadership in every sphere and at every level of governance. In fact, the controls and restrictions are only strengthening under a new leadership that is more absolute than any that China has seen since Mao Zedong who died more than four decades ago. Besides, China, given its current ideological trajectory of growth in power and influence, sees only potential losses and weakening, not gains and strengthening, from striking any conciliatory deal, whether with Tibetans on an ethnic minority issue, or with its own people on democracy and accountable governance, or even internationally, such as with India on the border dispute.

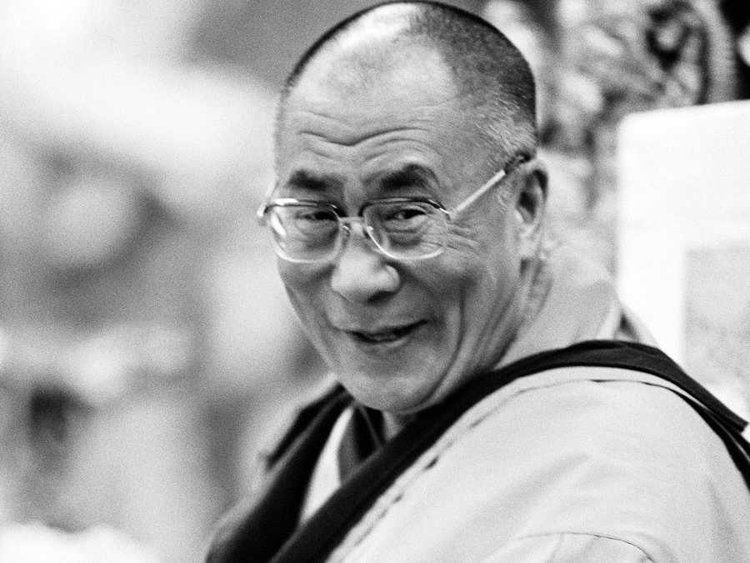

China’s most charitable offer to the Dalai Lama in any presumable talk would be nothing more than that made by party General Secretary Hu Yaobang back in 1981 (Jul 28) in his Five-Point Policy Towards the Dalai Lama: the terms on which the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet, sans any Tibet issue, might be allowed to come and live in Beijing. That policy was rejected by the Tibetan side then because it “reduced the issue of Tibet to the personal status of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.” And the stand of China’s current leadership is that the Dalai Lama has not done enough yet to earn such an offer.

If the Dalai Lama still continues to be ready and willing to engage with China, it is firstly because he considers having a contact to be better than continuing with the existing state of limbo, and, secondly, because he hopes to thereby gain a window of opportunity to channel the focus of the talks in the direction of the Tibet issue rather than just on his personal future, which is itself an enormous task.

Given this reality, it does not seem to matter very much whether Professor Samdhong Rinpoche, whom the Dalai Lama recently presented as one of his personal emissaries, did or did not make the visit. Indeed, the professor himself is said to have denied having made any such visit, although it was not clear in what context or clarity or obfuscation or plain-talk simplicity of terminology he had sought to dispel this supposed speculation. The remark was said to have been made to and reported by the Hindi daily Amar Ujala Dec 17.

Nevertheless, those who have commented on the issue in learned media and academic discourses have been in no doubt that the visit, in all likelihood, did take place. To begin with, the President of the Central Tibetan Administration at Dharamshala, India, apparently caught off-guard with the question during a Dec 14 memorial lecture in New Delhi, seemingly admitted that the visit took place while hastening to make the point that it was nothing about Sino-Tibetan talks anywhere near being back on track. “Don’t read too much into it. At most it’s a private visit and it’s too early to say anything,” the tribuneindia.com Dec 15 quoted him as saying.

With this dismissive note, the president has reportedly even gone to the extent of saying that Professor Samdhong Rinpoche had travelled to the Wutai Mountains area in Shanxi Province, sacred to Tibetan Buddhists as well for being the earthly abode of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of wisdom, and located about 350 km from Beijing, for the meeting. The Dalai Lama has, on occasions, expressed an ardent wish to undertake a pilgrimage there.

What initially set the speculations rolling was a commentary by India’s former ambassador to Mongolia and Tibet scholar P Stopdan carried by the website thewire.in Dec 4. Presenting the prospect for a Dalai Lama visit to China or Tibet being better now than ever before in a “rapidly-unfolding scenario”, he said the Dalai Lama “appeared to have” sent Samdhong Rinpoche on a discreet visit to Kunming, capital of China’s Yunnan Province. He went on to add that the visit had started in mid-November and was most likely facilitated by no less than You Quan, newly-appointed head of the United Front Work Department of the Communist Party of China that overseas Tibetan affairs.

You, he noted, had formerly served as party secretary of Fujian, was a close associate of President Xi Jinping, and had earlier successfully dealt with Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan’s business communities.

Another commentary cited “credible sources” as confirming that Professor Samdhong Rinpoche had visited Gyalthang (renamed by China firstly as Zhongdian and more recently as Shangri-La), his hometown in what is now part of China’s Yunnan province. And the purpose of the visit was stated to be to meet his family.

Whatever be the case, the arguments being advanced for the Chinese leadership being ready to engage with the Dalai Lama through his envoys is unexceptionable from the point of view of the supporting circumstances that have been cited to make the case for it. Nevertheless, the opposing supervening set of circumstances negating the plausibility of such an assumption, especially in terms of resolving the Tibet issue, is overwhelming and surely deserves to be taken into consideration with even greater amount of weightage.

When the whole picture is thus taken into account, any contention arising from one set of courses of recent developments that show that China may now be contemplating nothing less than resolving the Tibet issue is to indulge in a bit of reductio ad absurdum. Not only is China not a democracy but its leadership considers any embracing of a liberal democratic ideology, which is what resolving the issue of Tibet imperatively requires, the beginning of the end of the China as we know it today and which the Chinese leadership has vowed to prevent at any cost to enable the country to become the world’s top military and economic power. As to whether a dictatorial authority can attain and retain forever the pinnacle of global powers, the issue is only of academic importance at this time.

China’s only interest in seeking to win over the Dalai Lama is to control his reincarnation and thereby seek to gain effective control over the Tibetan population with a semblance of legitimacy. As regards Tibet, it considers the issue to have been resolved by a succession of historic events: the 17-point agreement of 1951, the dissolution of the “local” Tibetan government in 1959, and, finally, by the establishment of the so-called autonomous region of Tibet in 1965. This is the argument it has advanced in the past in response to the Tibetan side’s call for a “one country, two systems” arrangement like in the case of Hong Kong. As a matter of fact, China’s focus in the case of Hong Kong is seen to be increasingly on the “one country” aspect of this arrangement amid fears that the special administrative region’s fate seems to be destined to be no different from that of Tibet today.

And so, given the absence of any interest on the Chinese side to resolve the issue of Tibet, the task before the exile Tibetan leadership and people, as well as their supporters, is naturally not so much to bring the leadership there to the negotiating table – given the utter futility of it – as to keep the Tibet issue alive and bristling without being reined in by any uncalled for fear of angering Beijing based on uncalled for assumptions. The agenda would seem to have to be to carry forward an all-out movement with a sense of self-respect and with the impetus of a people in a grim life-or-death struggle rather than one having the luxury to sensitise that struggle to suit the mood of the enemy that keeps gnashing its teeth as it keeps eating one up alive. This would seem to be the message underlying the protest self-immolations that keeps taking place in Tibet today despite all threats and collective punishments from China and appeals from Tibetan leaders against such protest actions.