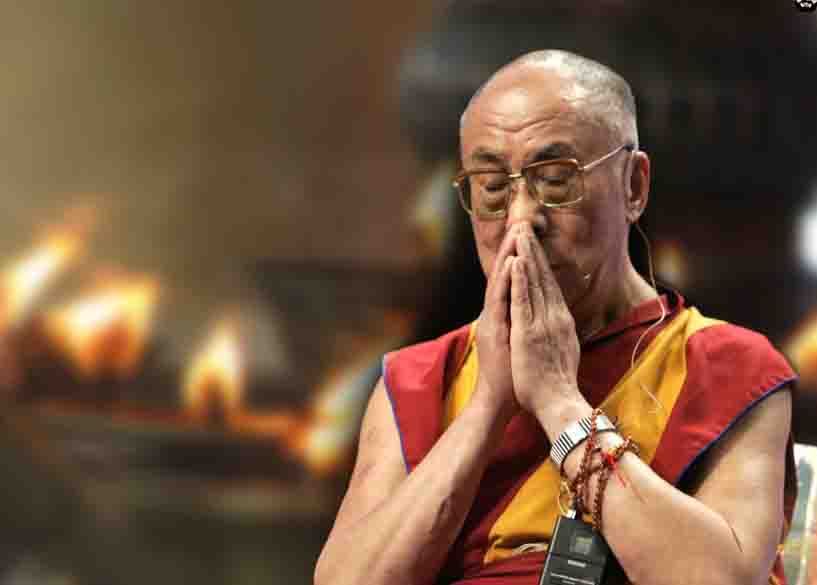

The Tibetan reincarnation tradition is more then 800 years old. Communist-ruled China is only 70 years old while the offering of a golden urn by a ruler of the Manchu dynasty, historically seen by the Chinese as foreign rulers, for suggested use in the reincarnation recognition process happened only sometime between 1791 and 1793 AD. And yet, atheist Chinese leaders, who do not believe in reincarnation, claim centuries-old historical right to determine the next Dalai Lama, points out Kunsang Thokmay*

(TibetanReview.net, Dec05’19)

In late October 2019, Sam Brownback, the United States ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, reported that he had told the 84-year-old Dalai Lama that the United States would seek to build global support for the principle that the choice of the next Dalai Lama should “belongs to the Tibetan Buddhists and not the Chinese government”. Two weeks later, on 11 November 2019, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang (耿爽) accused Washington of “using the UN to interfere in China’s internal affairs”, and repeated the old official narrative that “the reincarnation of living Buddhas including the Dalai Lama must comply with Chinese laws and regulations”.

Why do these powerful countries have a stake in a Tibetan Lama? The US, perhaps, intends to highlight the reincarnation so that the 15th Dalai Lama could be chosen freely, and plus China could not use the next Dalai Lama for its political propaganda. Beijing, on the other hand, obviously wants the 15th Dalai Lama to legitimise its rule over Tibet and accumulate the loyalty of Tibetans. Otherwise, why does China work so hard to get the ownership of a man that they regard as “a separatist devil” and a “wolf in monk’s robes”.

This deadlock of reincarnation politics is not a new story. On 29 July 1997, the Dalai Lama publicly stated that “if the Dalai Lama passed away while he is still in exile and [Tibetan people] want to find his reincarnation, then, I will confirm here that the next Dalai Lama will be born in a free country, not in China”. But he knows that China will not accept his proposal and they most probably will appoint another Dalai Lama as it did with the Panchen Lama. “Then there will be two Dalai Lamas: one, the Dalai Lama of the Tibetan heart, and one that is officially appointed”, said the Dalai Lama. As a response, Beijing declared the State Religious Affairs Bureau Order No. 5, which states that all the reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhism must get Chinese official approval. Otherwise, they are “illegal or invalid”.

Does it really work that way? On 14 May 1995, the Dalai Lama announced Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, a village kid in Tibet, as the reincarnation of the 10th Panchen Lama, the second-highest Lama in Tibet. After three days, the child Panchen Lama with his family suddenly disappeared in China. Then, Beijing appointed its own Panchen Lama, Gyaltsen Norbu, son of two communist party members. Despite the numerous efforts of China, Tibetan Buddhists never, even after 25 years, believe in Gyaltsen Norbu as the true reincarnation of the 10th Panchen Lama.

On several occasions, the Dalai Lama said that his reincarnation “will cease and there will be no 15th Dalai Lama” if the Tibetan people feel it is not relevant. Many political scientists think this is Dalai Lama’s way to signify the vitality of Tibetan people’s freedom of choice. China, however, took it the opposite direction. The frustrated Pema Trinley, the governor of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, responded that “Whether [the Dalai Lama] wants to cease reincarnation or not …. this decision is not up to him”. The governor also accused the Dalai Lama of “profaning religion and Tibetan Buddhism” by spreading such statements.

So, it seems China even wants to control which Lamas should or should not be reborn after their demise. Sikyong Lobsang Sangay, the prime minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile, said: “It’s like Fidel Castro saying, ‘I will select the next Pope, and all the Catholics should follow'”. In 2016, China launched an online Living-Buddha Authentication database, which excluded most of the Tibetan reincarnations in the diaspora, including the Dalai Lama. Beijing declared that whoever is listed in the database are authentic Lamas, and the others are fake. For Chinese communist leaders, it might be logical to ban the spiritual and religious practices if they do not serve material and political purpose.

Should not Tibetan Lamas have the authority to decide their reincarnations? Historically, the Lamas kept sole legitimate authority to determine their reincarnations. Tibetan Lamas often leave letters or oral instructions or other indications to recognise the next reincarnations, and sometimes Lamas choose their successors while they are still alive; the system is called “ma-dhey tulku”. Some well-known Tibetan Lamas even decided to cease reincarnation such as Sakya Pandita, Jetsun Milarepa and Tsongkhapa. In recent years, Jigme Phuntsok Jongnye, the first Khenpo of Serta monastery, publicly declared that he wouldn’t have rebirth. Tibetan Buddhism has so many such examples in history.

In such circumstances, Tibetan Buddhists always respect these decisions, and no one would dare to alter the “divine verdict” of lamas. Generally, the philosophy of reincarnation is a significant Mahayana Buddhist doctrine that Buddhists firmly believe Lord Buddha himself was the reincarnation of Svetaketu (Dampa Togkar) from Tushita realm. However, Tibet happened to be the first country to bring the philosophy in practice and developed it as a systematic reincarnation tradition. In 1204, beginning of the 13th century, an extraordinary child from Kham Derge was recognised as the reincarnation of the first Karmapa Dusum khyenpa. Since then, the tradition of reincarnation became increasingly systematic and has functioned without ceasing for more than 800 years.

However, the barely 70-year-old communist party of China knowingly do not want to accept this reincarnation tradition because this decision highly depends on the future reincarnations of Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas. For China, the reincarnation of the current Dalai Lama is an incredibly significant political issue, because many Chinese leaders calculate that Tibetan struggle is entirely depending on the Dalai Lama. Beijing’s Buddhist diplomacy is controlling the future Dalai Lama and make it its political tool to suppress Tibetan freedom struggle and enhance their Buddhist soft power.

On the other hand, the Dalai Lama lives in India and claims that “Tibet is historically and culturally closer to India than China”. As a geopolitical rival, it must be painful to hear such endorsements of India from a Tibetan leader like the Dalai Lama. At the same time, India uses the Dalai Lama to reaffirm their legal ownership over Arunachal Pradesh, a controversial territory between India and Tibet.

Because of all these reasons, in January 2019, China announced a five-year plan to increasingly sinicise the religions in China, including Buddhism, and make them more “Chinese” and more compatible with “Socialism”. In the beginning, people are confused; it seems no one has a clear answer what does this plan means? But, as always, President Xi has the final answer; he commanded that religious leaders in China must “love their country, protect the unification of their motherland and serve the overall interests of the Chinese nation”.

In recent years, China repeatedly claims that “the reincarnation of Living Buddhas as a unique institution of succession in Tibetan Buddhism is governed by fixed rituals and historic conventions”. The spokesman of the Chinese Foreign Ministry recently emphasised that even “the institution of reincarnation of the Dalai Lama has been in existence for several hundred years” because of these fixed rituals and historical conventions.

What kind of historical conventions is China talking about here? To comprehend the question, first, we have to look into the history of Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. In the 1470s, child Gedun Gyatso was confirmed as the reincarnation of the 1st Dalai Lama Gedun Drupa. In the following centuries, the reincarnations of Dalai Lamas, like many other Tibetan reincarnations, followed the systematic Buddhist tradition. Then, between 1791 to 1793, after 600-year of reincarnation tradition in Tibet, during the reign of Manchu Emperor Qianlong, China claims that Manchu generals, who came to Tibet to support the Tibetan army to fight against the Gurkha force, suggested the use of the “golden urn” method (喇嘛说) to select reincarnations of Dalai lamas, Panchen Lamas and other Lamas with Hutuktu title.

However, Tibetans hardly ever used the “golden urn” to confirm Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas. Under some exceptional circumstances, the Tibet government announced a few reincarnations such as the 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas and the 10th Panchen Lama as if the by results of golden urn selection to humour Manchus’ expectation; but the actual reincarnation selections were already confirmed as per Tibetan religious tradition. Otherwise, Tibetans never regarded “golden urn” as a sole legitimate selection method because as the Dalai Lama said, golden urn “lacked any spiritual quality”.

China also claims that “golden urn selection” is a part of the 29-point regulations (钦定藏内善后章程二十九条) suggested by the Manchu officials. But most of the scholars now agree that the 29-point regulations is the fabrication of communist China; that there is not enough evidence that Manchus made this kind of regulations. Regarding the golden urn method, Liu Hancgeng (劉漢城), the frontline Chinese history scholar, stated that the selection method is actually Tibetan traditional Zen Tak, the manner of divination employing the dough-ball method to recognise reincarnations. The Manchus, indeed, supplied a “golden urn” to make Tibetan Zen Tak tradition more visible.

Even if the golden urn selection method is supposed to be a part of Manchus’ legacy in Tibet, communist China do not has the rights to claims this legacy. Firstly, the Qianlong emperor was a learnt Buddhist himself and had priest-patron affiliation with Tibetan lamas, including the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, which is very different from the current relationship between atheist Chinese leaders and Tibetan Lamas. Secondly, Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, repeatedly urged the Chinese people to be united and “drive the barbarian Manchus back to the Changbai Mountains”. Thus, communist leaders viewed the Machu as a feudalist foreign invader of China. They even imprisoned, Puyi, the last emperor of Manchu. Thirdly, communist China never kept any of the traditional norms of the relationship between Dalai Lamas and Manchus, of mutual respect maintained for centuries. It is not surprising that China only highlights those norms which serve their interest and do not care about other related historical practices.

In 1954, Chairman Mao, the founding father of communist China, advised the then young Dalai Lama that “Religion is a poison” and Tibet should get rid of it because the monastic system hobbles population growth and the faith neglects material progress. It seems the communist party do not want to involve with this poison. However, Mr Xi took the opposite direction and declared that “only the Chinese communist party can confirm the authenticity of Tibetan Tulkus [reincarnations]”.

Telling the truth, this kind of policy is very inappropriate for a country like China, which explicitly rejects even the idea of past and future lives, let alone the concept of reincarnate lamas. But, in reality, China desperately wants an undisputed Tibetan Buddhist leader, who is loyal to the communist party. Robert Barnett said, “This is one of the chief indicators that China has failed in Tibet. It’s failed to find consistent leadership in Tibet by any Tibetan lama who is really respected by Tibetan people, and who at the same time endorses Communist Party rule”.

As the Dalai Lama ages, the diplomatic row over reincarnation politics is increasingly loud and aggressive, and from Washington DC to Beijing and Geneva to Dharamshala, everybody has something to say about the future of the Dalai Lama. No matter whatever the result might be. China is obviously not ready to give up the challenge against the Dalai Lama.

China answered the quest of the UN Human Rights Council regarding the disappeared Panchen Lama that “he [Panchen Lama] recently graduated from a university and even got a decent job now”. If that is true, China might use the 11th Panchen Lama, recognised by the Dalai Lama, to claim for the authority of choosing the 15th Dalai Lama. Traditionally, the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama often help to identify the reincarnations of each other. However, the Dalai Lama already carefully calculated all the possibilities and planned everything in advance regarding his reincarnation.

The Dalai Lama said that the responsibility of searching the 15th Dalai Lama “will primarily rest on the concerned officers of the Dalai Lama’s Gaden Phodrang Trust. They should consult the various heads of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions and the reliable oath-bound Dharma Protectors who are linked inseparably to the lineage of the Dalai Lamas. They should seek advice and direction from these concerned beings and carry out the procedures of search and recognition in accordance with past tradition. I shall leave clear written instructions about this. Bear in mind that, apart from the reincarnation recognised through such legitimate methods, no recognition or acceptance should be given to a candidate chosen for political ends by anyone, including those in the People’s Republic of China”.

However, as Germany Kent said, “no one else knows exactly what the future holds” and reincarnation politics will undoubtedly continue into the future. So, wait and watch!

—

* Kunsang Thokmay is a PhD scholar in Oriental Studies at Oxford University

* Kunsang Thokmay is a PhD scholar in Oriental Studies at Oxford University