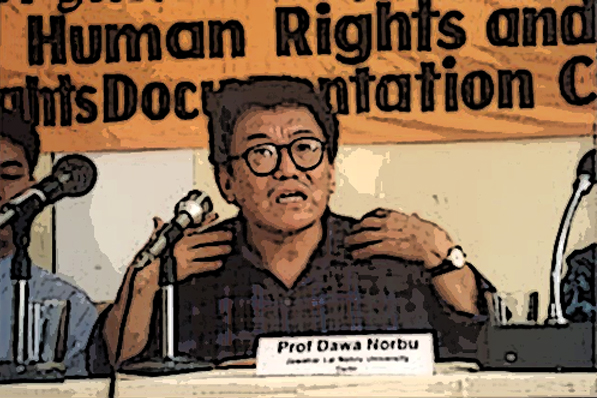

Dr Tashi Rabgey, Research Professor of International Affairs, George Washington University, in her keynote address, lauds Prof Dawa Norbu as the first modern Tibetan social scientist who in his long and quiet journey through the halls of academia had demonstrated the will to be disciplined by a different tradition of knowledge – to speak in a brand new way – so that a Tibetan could appear in a discursive space in which Tibetans had not previously been present.

Dr Tashi Rabgey, Research Professor of International Affairs, George Washington University, in her keynote address, lauds Prof Dawa Norbu as the first modern Tibetan social scientist who in his long and quiet journey through the halls of academia had demonstrated the will to be disciplined by a different tradition of knowledge – to speak in a brand new way – so that a Tibetan could appear in a discursive space in which Tibetans had not previously been present.

This article appeared in the Special Issue 2018 edition of the Tibetan Review, published in association with the JNU Tibet Forum. Keynote address by Dr Tashi Rabgey at 2nd annual symposium in memory of Prof. Dawa Norbu organized on April 7, 2016.

It is an honor for me to share some reflections on Professor Dawa Norbu, a defining scholar of contemporary Tibetan affairs and a deeply respected – and indeed, beloved – intellectual of Tibetan exiled society.

Let me start today by commending the JNU Tibet Forum organizers for convening this memorial symposium. For many reasons, I personally appreciate this opportunity to give these public remarks. As it happens, when I received the invitation to be here, I had just returned from two months in Chengdu as a visiting scholar at Sichuan University where I had the chance to work with Tibetan graduate students.

Still fresh in my mind was a memorable evening with a group of Tibetan Ph.D. students when I spoke late into the night about Dawa Norbu-la and his remarkable significance to our public discourse on contemporary Tibetan affairs. I was caught offguard when a particularly bright student said, “If Dawa Norbu’s work is so important, then why have we never heard of him before?”

There are of course many complex reasons why Dawa Norbu and his legacy is so little known among Tibetans inside Tibet. From my own study of social and political thought in Tibet, I knew there were other exiled Tibetan writers who were indeed well known and whose works manage to circulate under the radar in scholarly and writerly circles inside. But it is also clear that Dawa Norbu’s work has generally been neglected – an unfortunate fact that underlines one of the key themes I would like to sound for this symposium, which is the epistemic gap between Tibetan public thought inside and outside.

But there were also a few straightforward answers to the young man’s question as well – one being that we, collectively, have simply not said enough about Professor Dawa Norbu and his legacy. Like so many others, I privately mourned the untimely loss of this singular Tibetan scholar, but publicly said little about his astonishing contributions to the fabric and character of our Tibetan public life.

So, back in Chengdu last fall, I promised this young man that when I returned to America, I would write something about Dawa Norbu-la for him, and other budding young Tibetan thinkers like him who were struggling to make sense of where we are in the predicament of modern Tibet.

With this conversation in mind, I gladly accepted the serendipitous opportunity to be here with you at JNU today. I am particularly glad because this symposium provides an auspicious occasion to express a long held view on my part, which is that we often miss the true significance of Dawa Norbu’s work to our public discourse on contemporary Tibetan affairs.

So, for example, when we refer to Dawa Norbu, as we often do, as simply one of our Tibetan intellectuals, we tend to gloss over the distinctiveness of his astonishing body of work. We simplify the pioneering efforts that set him apart from his contemporaries. And we leave unsaid Dawa Norbu’s particular significance to – and the specific place he now holds in – the history of Tibetan social and political thought.

All the rest of us owe him such a debt – whether those of you here who had the good fortune to be his students here in New Delhi, or those of you, like me, who were his students through reading his work. As researchers of contemporary Tibet, we are all, in some way, in conversation with Dawa Norbu’s singular work.

When you look at his writing on Third World nationalism, when you read his journal publications in political science, when you see him on these pages working out his own individual approach to thinking about Tibet – and particularly when you consider the sum total of this prodigious effort in light of what else was being said and done by other contemporaries at the time, it is clear that Dawa Norbu simply broke the mold.

Through his personal effort, Dawa Norbu made himself into something brand new under the sun: the first modern Tibetan social scientist. In his long and quiet journey through the halls of academia, he demonstrated the will to be disciplined by a different tradition of knowledge – to speak in a brand new way – so that a Tibetan could appear in a discursive space in which Tibetans had not previously been present.

My own first personal impression of Dawa Norbu-la was not unlike that of most people. I met him when he came to give a lecture at Oxford while I was a law student there two decades ago. My first impression then – besides that he seemed, by temperament, a particularly agreeable person – was that he was also extraordinarily reasonable. As someone who was caught up in the fire and brimstone of other Tibetan prominent writers of the day, I found my first meeting with Prof Dawa Norbu to be an entirely different experience. Here was a strikingly rational and deliberate mind on display – a curiously imperturbable mind.

It took me many more years to discern what lay beneath that highly reasoned exterior he projected. It was not until I had shifted my own research inside Tibet that I could appreciate Dawa Norbu’s defining personal quality. It was not, as it seemed at first impression, his “extraordinary reasonableness” – that, it turned out, was just his mode of analysis. Over the course of my own research on contemporary Tibetan affairs from inside Tibet, I came to see that Dawa Norbu-la’s true defining quality was his personal courage.

Because in order to remain committed to that deliberate and rational mode of analysis at a time of political polarization, Dawa Norbu had to be willing to stare down an abyss and question the very order of things. As a Tibetan studying contemporary Tibetan affairs – and China’s Tibet policy in particular – that meant taking ideas, belief systems and cultural norms to which he himself surely had attachments, and throwing them into existential crisis – all in hopes of reaching sturdier political ground in our discussions of modern Tibet.

My respect for Dawa Norbu deepened as I came to understand this. And the insight I drew from studying his work was helpful as I myself became increasingly engaged in research inside contemporary Tibet.

I outlined my own epistemic concerns in a paper I wrote in 2004 about the first open forum on Tibetan public affairs inside Tibet. For six months, NewTibet.com provided an uncensored online discussion in Chinese cyberspace of Tibetan citizenship and political identity, religion and the need for secularization and even autonomy and political rights. The discussions on NewTibet.com electrified Tibetans inside Tibet. And yet the emergence of this unprecedented Tibetan public forum inside the PRC was not noticed anywhere outside of Tibet.

I drew on NewTibet.com to make a larger point about the fundamental gap in our sense of things, inside and outside Tibet. The online forum raised questions about the limits of what we can know as observers positioned outside the discursive space of Tibet. And as such, it challenged our existing structures of knowledge relating to contemporary Tibet. But the question of epistemic murk I raised in that paper was not simply a challenge to the prevailing global system of knowledge production about modern Tibet. It was also a challenge I set for myself in reaching for a sharper grasp and understanding of contemporary Tibet.

So, in the spirit of what Dawa Norbu called in Red Star over Tibet seeking out “what really went on in Tibet,” I stopped writing altogether and instead spent the next ten years quietly traveling to Tibet – seeking answers to those questions I could not, in good conscience, answer in 2004.

What I learned in that decade of conducting fieldwork changed how I saw the question of Tibet – and what I believed was possible for Tibet’s future prospects. My research on institutional politics on Tibet policy, in particular, overturned for me many of the key assumptions routinely and uncritically made by global scholarship about the prospects for the Tibet question in the PRC.

These included, for example, the assumption that Chinese researchers would refuse to participate in a formal discussion about Tibet that encompassed the so-called “Greater Tibet,” as it was considered a foregone conclusion that they would only ever countenance the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) as under discussion in matters concerning the Tibet issue. It was also long assumed that PRC scholars would not be willing to discuss at international meetings issues of policy inside Tibet. For this reason, global academia long discouraged the pursuit of policy research in the study of contemporary Tibet.

But from my work on governance research in Tibet, I came to know that these and other cardinal assumptions made by global Tibet scholarship were simply untrue. My years of observation and exploration in Tibet – as well as in Beijing and elsewhere in the modern Chinese state – showed me that there was much we were not getting right, and that a serious rethinking was necessary in our basic framework in the study of contemporary Tibet politics.

While this work of shifting our discourse is still unfolding, I wish I had the opportunity to thank Dawa Norbu-la now and tell him the role his life’s work has played in my own search for new research frontiers in the study of contemporary Tibet. His example and unyielding spirit in exploring the edges of our known Tibetan discursive world had a great impact on me – as it has had on so many of us.

I believe it must have brought Dawa Norbu-la great satisfaction knowing the legacy he would leave behind in you all – a new generation of young Tibetan scholars taught and trained here at JNU.

Likewise, I wish he could have also known your counterparts in Tibet – a rising generation of young Tibetan thinkers who are seeking clarity in the slippery and uncertain Tibetan world inside. I believe their missing voices would have brought Dawa Norbu a refreshing sense of hope – just as I believe knowledge of his life and work will shine a new light of awareness in these young Tibetans’ search for their own understanding of our modern Tibetan predicament.

It is my hope that all of you who represent the next generation of Tibetan scholars, writers and public thinkers – inside and outside alike – will be inspired by Dawa Norbu’s life story as I have been. His achievement in forging new ground in contemporary Tibet scholarship was a remarkable feat not only of hard work and industry, but also of extraordinary imagination.

It is precisely that force of imagination, together with hard work, we will all need to call upon now to see past the many barriers that separate us. And it is only in transcending those boundaries that we can begin to write a new shared chapter in the unfinished story of modern Tibet.