By Morris Tennyson

(TibetanReview.net, May09’20)

A Tibetan exile orphan raised in Europe who returned to Tibet to establish orphanages and centres for the children of nomadic herders has died this week in Switzerland of COVID-19.

Tendol Gyalzur, who was originally from Shigatse, lost her parents and brother while crossing the Himalayas as they escaped to Bhutan and onto India in 1959. But after being adopted into a German ‘children’s village’, and living in Switzerland, she came back to Tibet in the 1990s, setting up homely orphanages for abandoned children in Lhasa and Shangri-la (Gyalthang), and a centre for nomadic children in western Sichuan.

Over a quarter of a century, she was a surrogate mother to around 300 children, many who are now adults. Tendol leaves behind a legacy of love, a testament to how one person against the odds can make a difference to the lives of many. Modest about her achievements, and quick to acknowledge the support of her family, friends, sponsors and volunteers, Tendol managed to negotiate her way through the paperwork, suspicion, and obstacles by being open, building networks of supporters including government officials, and demonstrating the benefits of non-institutional care for children who had lost their parents or who were found on the streets.

After growing up in Germany and Switzerland, and having married a fellow Tibetan and starting a family, Tendol returned to Tibet for the first time in 1990, when she was in her mid-30s, and her two sons were teenagers.

One life-changing incident in Lhasa near the Potala Palace highlighted a problem and challenged her to respond. She saw two dishevelled children rummaging through rubbish for food scraps. When she took them to a nearby place to eat, the manager at first refused to let them in and sit down.

“It was then, for the first time in my life, I realised that the only thing I wanted to do was fight for the rights of these abandoned children,” she said. “I know there are orphans all over the world, but I am Tibetan, and I wanted to help the orphans of Tibet.”

***

Back in Europe, still haunted by the images of the scavenging Tibetan street-children, she mentioned her dream of establishing an orphanage in Tibet; but her family and friends in Switzerland and Germany were sceptical, saying it would be too difficult for the surgical nurse with limited funds to set up a private institution in bureaucratic and xenophobic Communist China.

Undeterred by the objections, she took out her savings and her husband’s pension, sought donations and loans from family and friends, and secured some financial support from the Tibet Development Fund.

Within three years of that pivotal moment in Lhasa, she returned in 1993 to open Tibet’s first private orphanage at Toelung just outside Lhasa. It started with just six children. She opened a second orphanage in her husband Losang’s hometown of Shangri-la in 1997, and five years later established a centre in western Sichuan for the children of nomadic herders.

Her accomplishments fulfil the words of the Dalai Lama, who spoke to a group of children including Tendol before they were sent from refugee camps to Europe. His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama prophesied that they were like flower seeds, that would later bloom in Tibet, and urged them to share their happiness with others.

***

After growing up near Konstanz on the German-Swiss border, Tendol married Losang, who had fled to Switzerland in the early 1970s, and together they moved to near Zurich. One of her sons went on to become a professional ice hockey league player, later moving to Shangri-la to establish cafe-bars and restaurants, as well as a brewery, the Shangri-la Highland Craft Brewery, which has 80% of its staff on apprenticeship and training schemes from the orphanage, learning skills for the tourism-oriented economy of north-west Yunnan. Losang, a trained electrician and fine horseman, moved to Shangrila to help Tendol with her mission, which was inclusive to include not just Tibetan children, but those from the other minorities which make up the Tibetan borderlands.

As well as taking any children in need, referred by the local agencies, Tendol pushed for more support and resources from the government. Initially, she was supported by organisations such as Seattle-based Global Roots, founded by Rick Montgomery, who first met Tendol in 2001, and has provided winter clothes, food, blankets, kitchen supplies, and bicycles to her homes. “She is one of the most amazing, selfless women I have ever met. Her work inspired me to start Global Roots, which supports charities across the world.”

Tendol’s charity was aided by supporters in Europe, particularly in Switzerland, Germany, Austria and France, with some donors visiting the orphanages in Lhasa and Shangri-la to see for themselves the caring environment created with gardens, house-parents, pet animals and volunteers. Tendol travelled between the three endeavours, heading back to Switzerland to report on progress and raise more funds for expansion (both Lhasa and Shangri-la facilities were home to over 50 children), better facilities, and in some cases, medical operations for young residents.

Concerned about the loss of Tibetan language among children in Tibetan-speaking areas, she found teachers to give classes after school or doing the weekends, with Chinese and overseas volunteers also helping improve the children’s written and spoken language. The children learnt traditional Tibetan songs and dances, and in Shangri-la after a new performance hall was built, would entertain visitors with welcome songs and choreographed dances.

While Tendol was a Tibetan Buddhist brought up in Europe with Christian values, she was careful to allow the children find their own cultural and religious identity and values, rather than impose anything on those under her care. She was on a mission to save the children, but not convert them. In an interview she once said her work was practical and pragmatic rather than religious, ‘my religion is wiping children’s noses’.

Such was the reputation of her labour of love that the orphanages were listed in some travel guidebooks such as Lonely Planet, recommended as an organisation fostering awareness of Tibet and aiding the Tibetan people. The orphanages became beacons of cultural understanding, showing what many cultures and religions can do when they unite and set their minds to help children. “I’ve learned a lot from our children,” Tendol once said, “And I believe that others might learn from our children how to live in peace.”

Over time, Tendol gained the trust of local officials and also more resourcing. For example, in Shangri-la the local government more recently funded teacher salaries, and made guarantees for providing food, clothing, housing and transport, having been impressed by the model orphanage and its human-centred operation. With nationwide changes to the administration of orphanages, more onerous reporting requirements for foreign NGOs, and the better provision of social services, Tendol and Losang (who had both passed the 65-year retirement age) closed the Lhasa and Shangri-la orphanages in 2017 and 2018, with the remaining children now cared for by the official orphanages.

***

One of the features of Tendol’s orphanages, often noted by visitors, was the co-operation between children of all ages, with older ones caring for younger residents. They referred to each other as brothers and sisters. Another characteristic was the extra-curricular activities, which included monastery visits, hiking trips, sports and horse-riding. With Losang a renowned horseman, a number of the children learned the skills of Tibetan horse riding, with several winning prizes at Shangri-la’s annual horse-riding festival, one of the largest events in the region.

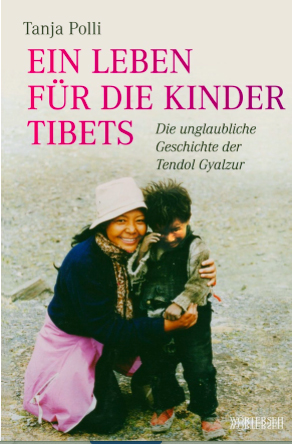

Tendol was proud of all of her children. Around the walls of her office, certificates and prizes awarded her children joined photographs of her Swiss family. Tendol had a big family that went beyond her own and her homes. The story of her struggles and successes was published last year in a book by Tanja Polli (in German) “A Life for the Children of Tibet – The incredible story of Tendol Gyalzur”. (www.woerterseh.ch/produkt/ein-leben-fuer-die-kinder-tibets/)

When news broke in early May of Tendol’s death from COVID-19 in Switzerland, there was an outpouring of grief and sadness around the world, with loving comments in many languages written by those who had been touched by the ‘super-mother ‘of Tibet. An announcement published in the Shangri-la media praised her outstanding contribution of selfless dedication to welfare, noting her ability to navigate through bureaucratic obstacles, and saying she was a great inspiration to others. “Love is boundless,” said the tribute, “And able to turn dry lands into a lush green pasture.”