By Nick Gulotta*

The Tibetan national flag is an internationally recognized symbol of Tibet’s independence dating back to the early 20th century, not simply a military symbol elevated to the status of a “national flag, which never existed before 1959” as claimed by Beijing and by their pseudo-academics in the West. Nick Gulotta seeks to open a new chapter in this recognition through further historical research.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Tibetan National Flag was internationally recognized and well known, despite Tibet’s geographic and self-imposed political isolation. While there is ample evidence of this, the Chinese government still maintains that “the Dalai Lama and his supporters” simply elevated a military symbol to the status of a “national flag, which had never existed before 1959.”1

This disproven claim, and its companion argument that the Tibetan nation state prior to China’s invasion was an invention by Tibetan exiles, has been championed by several western academics and in recent days by misguided social media personalities. One need look no further than Twitter to see posts by Beijing’s wumao or “50 Cent Party,” who are paid for comments propagating the state narrative and by pseudo-journalists who regurgitate these claims.

Historian, author, and freedom fighter, Jamyang Norbu, has written extensively about Tibet’s independent status and dispelled these myths about the Tibetan flag.2 He points out that before 1959, the flag was used inside of Tibet and recognized internationally in publications including one by the British Crown and in the September 1934 National Geographic Magazine.3 Inspired by that work, I set out to identify additional historical examples of recognition and awareness of the most recognizable symbol of Tibet’s independence—its national flag. Stemming from several years of research, this article seeks to contribute a new chapter to that history.

This research shows that despite the Chinese government’s claims, between the early 1920s and 1959, the Tibetan flag was included in dozens of flag reference books, world atlases, encyclopedias, and flag charts as a national flag representing an independent nation. Further, it shows that the flag was recognized by multiple governments and used by the international public.

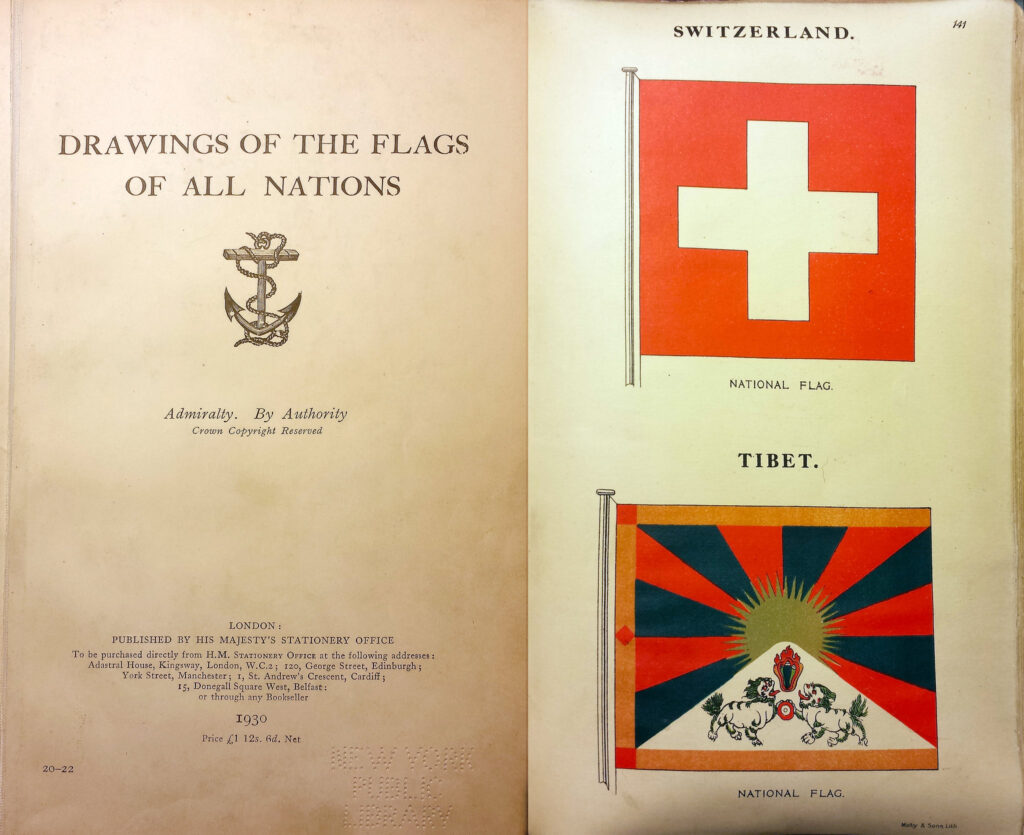

Tibetan flag was first inaugurated in 1916 by His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama at a military parade at the Norbulingka palace in Lhasa.5 Outside of Tibet, references to the flag first began appearing in newspapers by 1923. Multiple articles were written that described the flag after it debuted in an edition of the British Crown’s “Drawings of the Flags in Use at the Present Time by Various Nations” flag book. One example can be seen in an article from the San Francisco Examiner printed on December 16, 1923, titled “Nations Adopt New Emblems.”

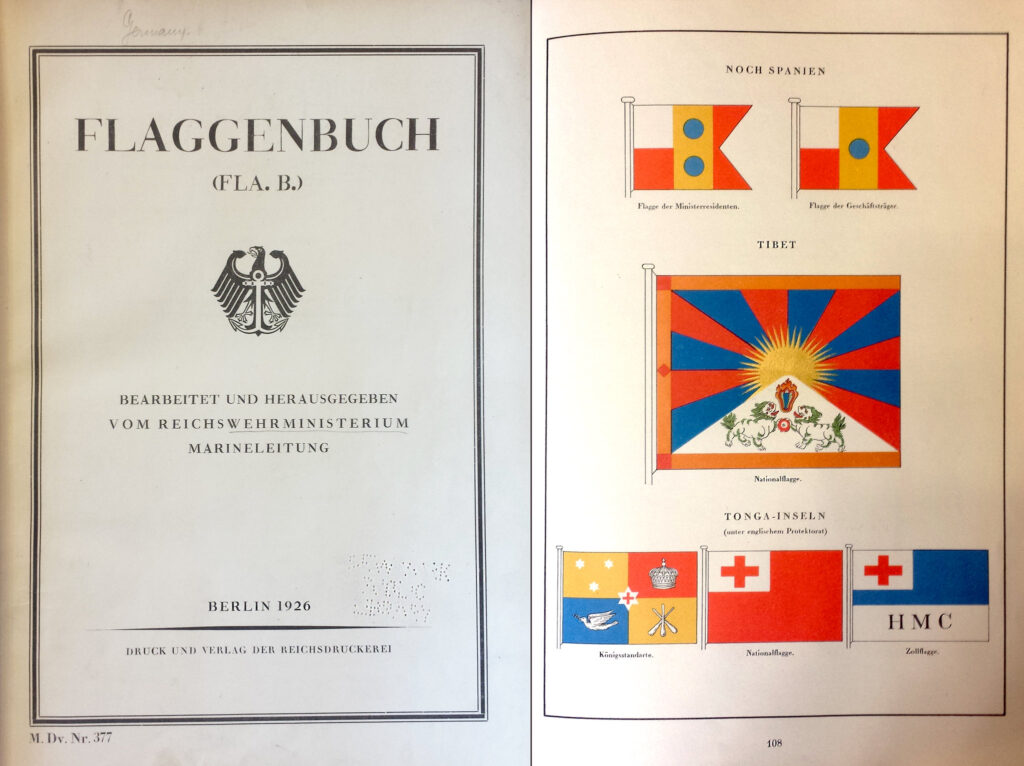

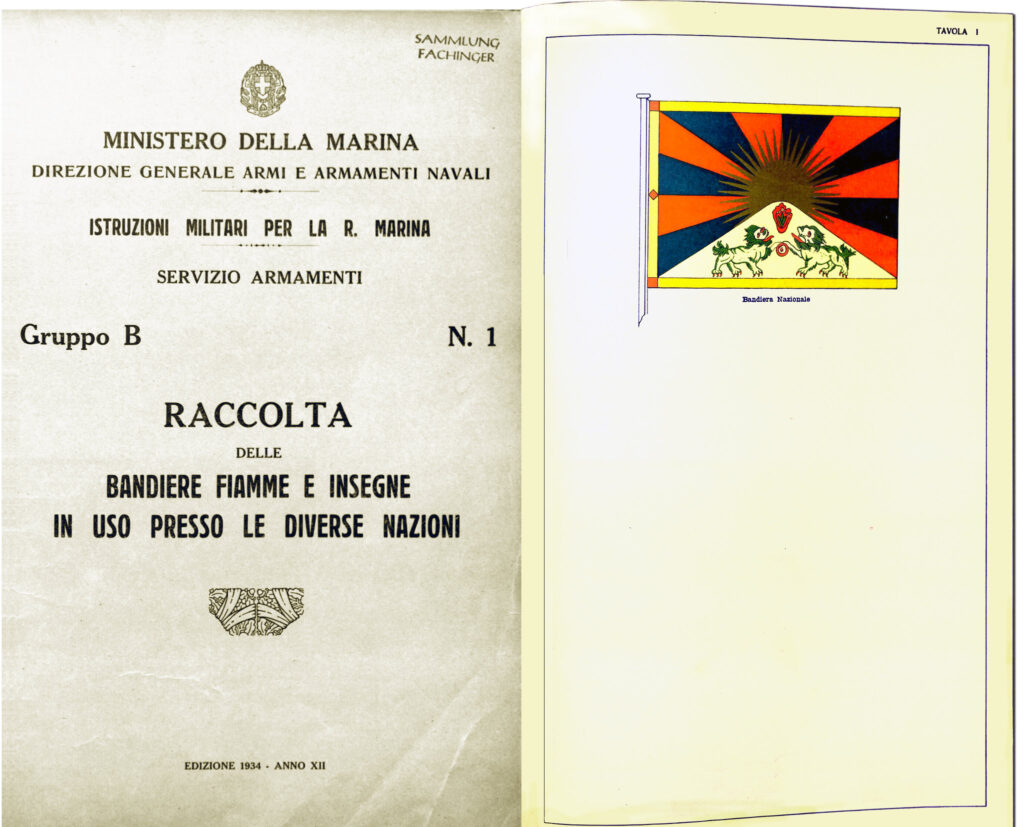

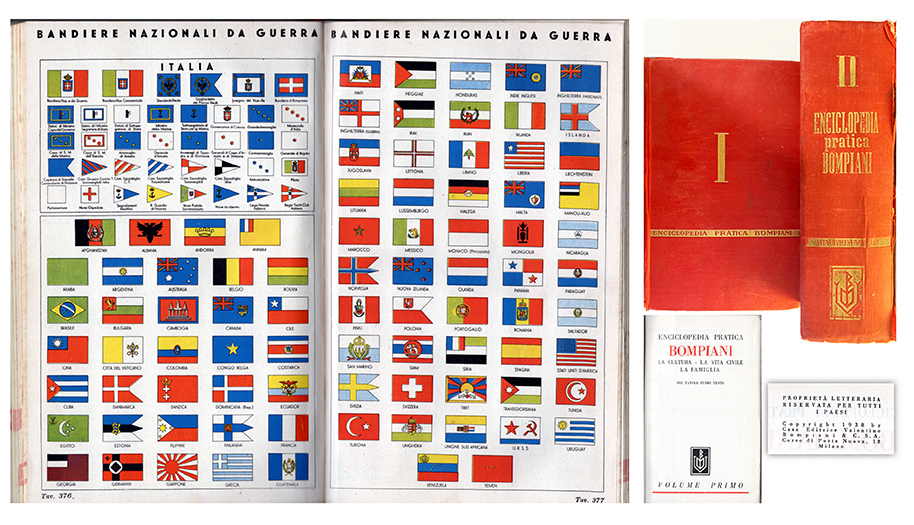

During this period prior to the founding of the United Nations, many flag reference books primarily featured the flags of global military or trade powers, colonies, or were published for maritime usage. Even though Tibet had relatively minimal foreign relations and military engagement, at least three foreign governments published military books that included the Tibetan flag. As mentioned above, an edition of “Drawings of the Flags in Use at the Present Time by Various Nations” was published by the British Crown in 1923; “Flaggenbuch” was published by the German government in 1926; and “Raccolta delle Bandiere Fiamme e Insegne in uso presso le Diverse Nazioni” was published by the Italian government in 1934. In each book, the Tibetan flag is referred to as a “national flag.” Editions of the British government’s flag book included the flag well into the 1950s. These books further underscore a well-documented recognition of Tibet’s de facto independent status.

Many readers may be acquainted with the official usage of the Tibetan flag at the 1947 Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi. The 10-day international conference was organized by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru where the Tibetan flag was hoisted amongst the flags of other nations and the Tibetan delegation sat behind a dais with a plate board displaying the national flag. The Tibetan Government in Exile has identified this as the flag’s “first appearance at an international gathering.” 6 7Another example where the flag was used to represent Tibet, albeit less international in nature, has more recently surfaced.

Nearly a decade after the Asian Relations Conference, His Holiness the Dalai Lama traveled to India in 1956 for the celebration of Buddha Jayanti, the 2,500-year anniversary celebration of the Buddha’s birth. While traveling through the small then-independent Kingdom of Sikkim, his motorcade entered the capital city Gangtok in a car provided by Chogyal (king) Palden Thondup Namgyal. His Holiness rode in the Chogyal’s personal sky-blue Buick convertible, which had a Tibetan and Sikkimese flag affixed to the front for the visiting head of state.8

Stunning footage Stunning footage recently restored and released by the Conserve Tibet Project, led by Thupten N. Chakrishar, shows the Tibetan flag flying on the same flagpole alongside the flag of Sikkim at the Chogyal’s Tsuklakhang Palace. While the deep relationship between Sikkim and Tibet prior to China’s occupation is a subject for its own article, the official usage of the flag by the Sikkimese government is another example of recognition of Tibet’s independent status.

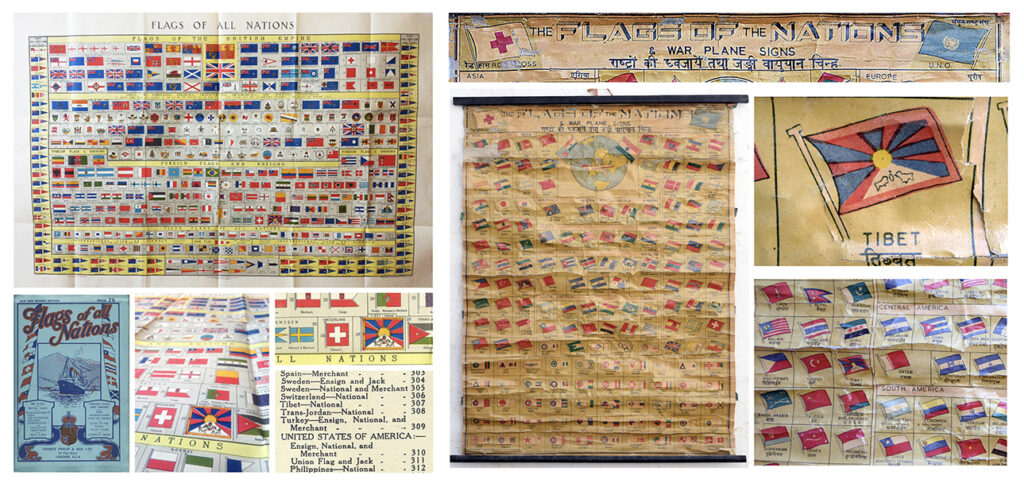

In addition to these examples of official recognition and usage, Tibet’s flag was included on multiple flag charts widely printed for maritime and educational usage between the 1920s and 1950s. One example was published in 1936 by George Philp & Son Ltd., one of the oldest British publishing houses. Another chart titled “Flags of the Nations and War Plane Signs” was printed in 1947 by Prem Educational Stores in New Delhi, India.

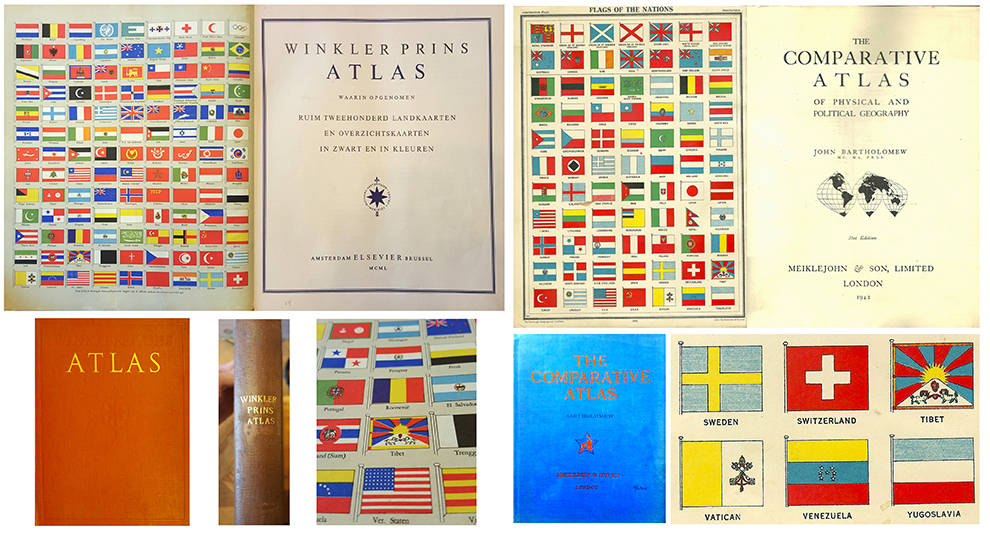

Additional examples where the flag appeared in reference books can be viewed in a collection that I have uploaded to the website Flickr under the username TibetanFlag. The examples include an Italian encyclopedia from 1938; a book of flags by British Vice-Admiral and a Member of Parliament Gordon Campbell from 1950; an Atlas by John George Bartholomew; Cartographer to H.M. King George V from 1942; a Dutch atlas from 1950; an Australian newspaper, and half a dozen other encyclopedic works that include the Tibetan flag alongside those of other independent nations. Over the next several years as the copyright expires on more reference books from this period and they are added to the public domain, I believe many additional examples will surface.

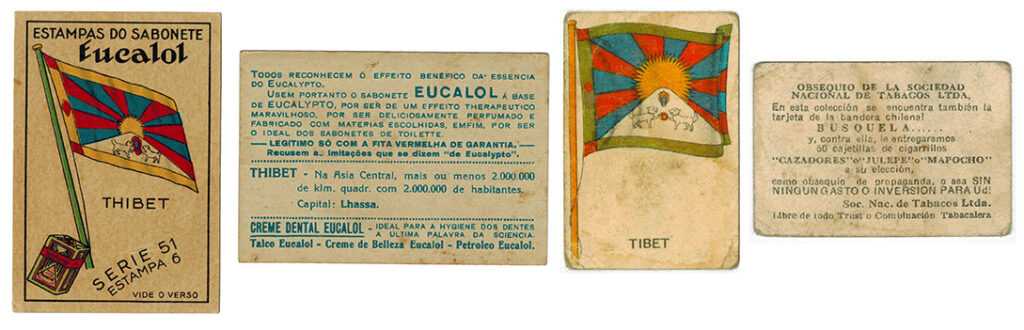

In addition to governments and academic publishers, the international public also widely used the flag. In a previous article that I co-wrote, I discussed the Tibetan flag’s appearance on trade cards, which were printed all over the world between 1928 and the early 1960s. Trade cards were ubiquitous collector’s items that often featured encyclopedic themes and were included with the purchase of products such as candy, soap, cigarettes, and in albums. Over 30 unique examples of cards that feature the Tibetan flag were widely printed in countries such as in Brazil, Chile, Germany, England, New Zealand, Turkey, Israel, Norway, Greece, and Italy. They prove a vast international awareness of the flag prior to China’s invasion of Tibet.

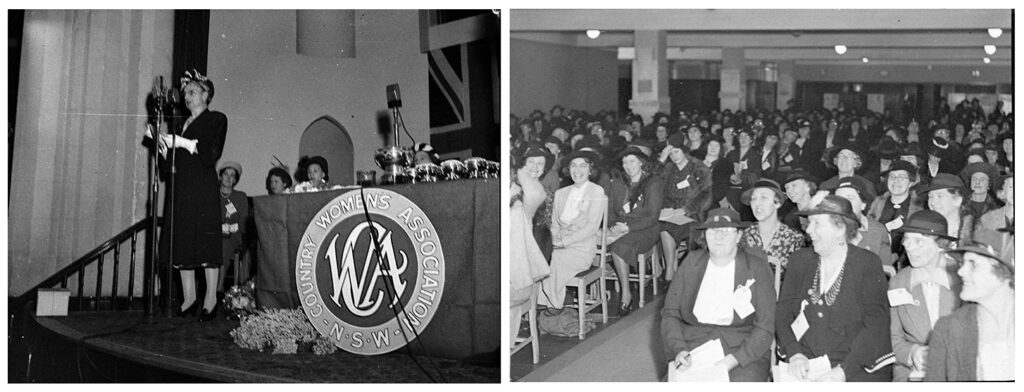

One previously unexplored example of the public’s use of the flag took place in Australia in 1940. That year, the Country Women’s Association (C.W.A), a social welfare organization, held their annual conference and State Handicrafts Exhibition in Sydney. As part of the event, the C.W.A organized a “flags of the world” display, which included a handmade 6-foot x 3-foot Tibetan National Flag made of “red, yellow, and blue satin, with a rising sun worked in gold thread.” Attached-to each flag were descriptions and details, concerning the origin and the country it represented.9 The exhibition was attended by thousands and the flags were put on display at several other C.W.A functions attended by government officials throughout the early 1940s.10 11

The event organizers remarked that the purpose of the exhibit was to ”inspire international spirit” among various CWA branches.12 Dozens of reports from these events in Australian newspapers describe the Tibetan flag as completely separate from the Chinese flag, representing two distinct countries. Underscoring the significance of the C.W.A’s flags display, the Chinese Consul General in Sydney got involved and advocated for the replacement of the Chinese imperial flag with the newer Nationalist flag. As a result, the imperial flag was “withdrawn from their display.” The local C.W.A president expressed regret for the incident, and said, “immediate steps would be taken to procure and display the truly national flag of China.”13 There is no mention of any official objection or debate about the inclusion of the Tibetan flag.

A physical Tibetan flag such as the one given to American journalist Lowell Thomas by the Dalai Lama in 1949 (pictured below) was almost certainly unavailable in Australia in 1940.14 As such, the C.W.A example encapsulates the public’s awareness and regard for the Tibetan flag. Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic and a move of the C.W.A archives, a photo of the flag display could not be provided for this article but I am sure one will surface in the future.

A. Cannavino Library, Marist College).

Despite an overwhelming number of primary sources, scholarship, and visual documentation from inside and outside of Tibet, Chinese government’s distortion of Tibetan history is still propagated by a small number western writers and academics. While these false claims have found new life on social media, facts are simply not on their side. The many examples where the international community recognized, printed, and even flew the Tibetan National Flag prior to 1959, fly in the face of these claims. Today, individuals, institutions, and governments who raise the Tibetan flag can be assured that their support is not only an act of moral and political solidarity but is also rooted in a clear history of international recognition of Tibet.

—

* Nick Gulotta is a New York-based public servant, community organizer, and longtime Tibet activist. He has a degree in Political Science from the City University of NY, Hunter College.

References

- “Commentary: Dalai Lama a Politician, Not a Simple Monk,” Commentary: Dalai Lama a politician, not a simple monk (Xinhua News Agency, March 31, 2008), http://www.china.org.cn/china/Lhasa_Unrest/2008-03/31/content_13946226.htm.

- Norbu, Jamyang. “Freedom Wind, Freedom Song.” Shadow Tibet Jamyang Norbu. Shadow Tibet , September 25, 2018. https://www.jamyangnorbu.com/blog/2015/02/12/freedom-wind-freedom-song-1/

- Norbu, Jamyang. “Early International Awareness of the Tibetan National Flag.” Shadow Tibet Jamyang Norbu, February 28, 2015. https://www.jamyangnorbu.com/blog/2015/02/28/early-international-awareness-of-the-tibetan-national-flag/

- The edition that first included the Tibetan flag was published with a longer title, “Drawings of the Flags in Use at the Present Time by Various Nations” in 1923.

- Tenzin Geyche Tethong, “His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama: an Illustrated Biography,” in His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama: an Illustrated Biography (Northampton, MA: Interlink Books, 2021), p. 33.

- “CTA’s Response to Chinese Government Allegations: Part Four.” Central Tibetan Administration. Tibet.net, June 19, 2008. https://tibet.net/important-issues/sino-tibetan-dialogue/ctas-response-to-chinas-allegations/ctas-response-to-chinese-government-allegations-part-four/

- Officially known as the Central Tibetan Administration.

- Duff, Andrew. “Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom.” Essay. In Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom, 85. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd, 2018. Also, the Tibet Museum in Dharamshala has published a photo of His Holiness being driven in the same vehicle through Kalimpong, India with the Sikkimese flag removed.

- Duff, Andrew. “Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom.” Essay. In Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom, 85. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd, 2018. Also, the Tibet Museum in Dharamshala has published a photo of His Holiness being driven in the same vehicle through Kalimpong, India with the Sikkimese flag removed.

- Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909 – 1954), Thursday 8 May 1941, page 3

- Warwick Daily News (Qld. : 1919 -1954), Tuesday 23 April 1940, page 3

- Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1878 – 1954), Thursday 24 October 1940, page 4

- Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909 – 1954), Thursday 29 May 1941, page 4

- From Lowell Thomas Papers: Tibet, 1949, Item 1, Box 1712, in the Lowell Thomas Collection, Archives and Special Collections, James A. Cannavino Library, Marist College.