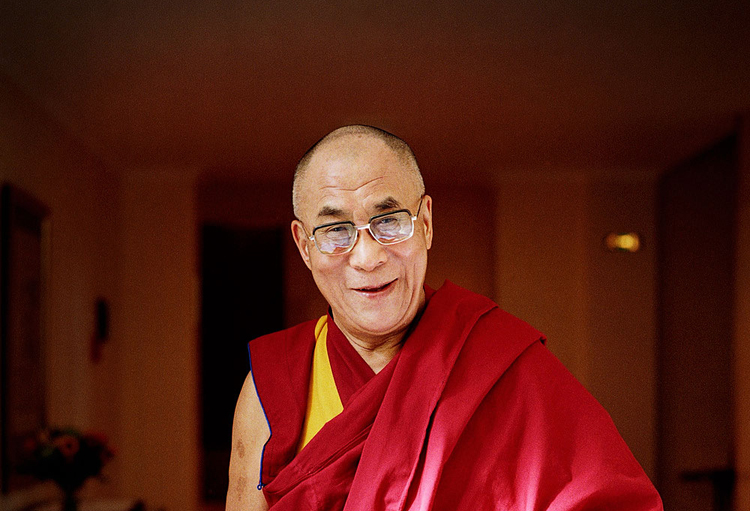

Kunsang Thokmay* argues that though the Dalai Lama fully deserves the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, New Delhi may be disinclined to respond positively to the ongoing clamour in favour of it in order to avoid a controversy on several grounds.

(TibetanReview.net, Apr26’19)

On 15 April 2019, the head of the All Party Indian Parliamentary Forum for Tibet (APIPFT), Mr Shanta Kumar, announced that the association had sent a petition letter to the Indian government to request conferral of the Bharat Ratna on the Dalai Lama. The letter was signed by around 200 MPs from twenty-five different political parties of India. On 30 March 2019, Ramachandra Guha, a Gandhian historian, wrote an article on “The Telegraphy” arguing that India should affirm their respect for the Dalai Lama by openly honouring him with the medal, counted as India’s highest civil honour. The same day, the current chief minister of Bihar state, Nitish Kumar, supported Ramachandra’s suggestion through his Twitter account, re-emphasising that India should recognise the Tibetan spiritual leader.

On 12 April 2019, former West Bengal governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi published a lengthy article in the ‘Naidunia’ newspaper demanding the awarding of the Bharat Ratna on the Dalai Lama. In the article, he argued that it was “strategically” important for India and it will send a “strong message to the international” community. Moreover, the Himalayan Culture and Religion Association officially announced that they would assist the campaign for the Bharat Ratna to be awarded to the Dalai Lama. All this has happened amidst the Bharat Ratna 2019 controversies. The family of late singer Bhupen Hazarika have signalled their intention to return the award in protest against the Citizenship Bill, whilst Prime Minister Modi has been accused of political opportunism in his selection of Pranab Mukherjee for the award. The furore is unsurprising: the Bharat Ratna always stirs up a hornet’s nest across India’s political and social spectrums.

However, the story has a much deeper history than just these recent events. The head of the Himalayan Committee for Action on Tibet, Lama Chosphel Zotpa, explained in an interview with the Voice of America (VAO), “we, the Himalayan Committee for Action on Tibet and the Himalayan Religion and Culture Association began to campaign for the Bharat Ratna to be given to the Dalai Lama in the 1990s.” They have been keeping the campaign up for decades. But, he thinks, the problem is “the political and social tendencies” in India.

Speaking in Dharamsala in 2016, BJP Lok Sabha MP Mr Shanta Kumar publicly requested the Bharat Ratna be granted to the Dalai Lama. The next year, on April 6, 2017, Lhundup Chosang, the regional head of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in Arunachal Pradesh told reporters, “the Dalai Lama deserves the Bharat Ratna as he has said that he is a son of India and feels honoured to be the longest-serving guest of this great country.” The RSS in Arunachal Pradesh even submitted a plea to the Prime Minister Narendra Modi, signed by 25,000 of this campaign’s supporters. However, a few days after that announcement, RSS spokesman Rajiv Tuli told reporters, “we have not started any official campaign demanding the Bharat Ratna for the Dalai Lama. These decisions are taken by the government.” The group, which champions the Hindutva ideology, swiftly withdrew their official connection with the Dalai Lama.

Now, the central question is why the Dalai Lama still has not received the Bharat Ratna after six decades of residing in India, tirelessly promoting Nalanda tradition in the world, firmly practising the Gandhian philosophy of Ahimsa and proudly declaring himself as a loyal son of India? To comprehend the issue, we have to address two other questions.

Firstly, does the Indian government think that the Dalai Lama does not deserve the Bharat Ratna? Absolutely not. As Ramachandra Guha has claimed, India knows that the Dalai Lama “deserves (this) more — far more — than many past recipients.” The Dalai Lama has received over hundreds of international awards from the Nobel Peace Prize to the US Congressional Gold Medal to Honorary Canadian Citizenship and so on. His contribution to the Indian Nalanda tradition exceeds that of any other contemporary Buddhist leader in the world. He has proudly announced that he is a son of India; he has been educated in Nalanda tradition and he survived most of his life eating dal and roti. He is also a firm believer in Gandhian philosophy of non-violence and, finally, he has always warmly expressed his gratitude to India and the Indian people for the welcome provided to him and his people. He is clearly amply qualified for the Bharat Ratna.

Secondly, is this because India is too scared of China? India, indeed, does care about China. China is India’s largest trading partner, and, also, one of the biggest and potentially most dangerous neighbouring countries. However, that is not the whole story. India allowed the Dalai Lama to visit Arunachal Pradesh eight times in the face of fierce objections from China. The current government officially invited Lobsang Sangay, the president of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile, to Rashtrapati Bhavan for the swearing-in ceremony of Narendra Modi and his ministers in 2014. India has firmly challenged Chinese road construction in Doklam and border intrusions. Moreover, China’s “continuing support for Pakistan’s terrorist actions against India surely calls for firmer action” and this strategically demands India to play their diplomatic game.

India has, indeed, many reasons to confer the Bharat on the Dalai Lama, for its strategy, morality and dignity. On the surface, it seems, India keeps a distance from the Dalai Lama because of China. But, in reality, India is far more cautious about bringing the topic of the Dalai Lama into the official realm due to domestic tendencies. Thus, the government knowingly keeps him far from Delhi and from other major social and political domains. Gopal Krishna Gandhi questions: “India treats the Dalai Lama as a jewellery box, keeps him aside, away from the public sight. We let the box asleep in the dust under the bed or in the corner of the house.” Tibet and India expert Claude Arpi thoroughly analysed the long-term motivations of the Indian government to keep a distance from the Dalai Lama.

In a Hindu majority country, giving leverage to a Buddhist leader who also happens to be a foreigner might cause unnecessary domestic cultural clashes and discontent among the Indians and Indian religious leaders. Although Buddhism originated in India, the fundamental philosophy of Buddhism does not match very well with Hinduism. Intellectual debate between Buddhist and Hindu scholars has been a centuries-old tradition on Indian soil. Perhaps, it sounds naïve, but at this time of radical Hindutva ideological campaigns, many Indians do not want to hear any voices other than Hindu voices. So, for the political parties, this is a serious issue which has the potential to impinge on their electability.

The Dalai Lama genuinely believes that India is an ideal place for religious harmony. He argues, “there are various religions and traditions in India. It has a population of over 125 crores. Muslim countries should learn from India so that there is peace. There is coordination among all the religions here, and, due to the principle of non-violence”. He, himself, has always wholeheartedly promoted religious harmony. Along with the Hindu religious leaders, he also maintains close relationships with Indian Muslim religious leaders, often sharing platforms with them. His arms are always open and he welcomes adherents of other religions. However, the current BJP-led government and its allied groups such as RSS are extremely sceptical on issues concerning the equal treatment of Indian Muslims. So, it is a natural instinct for them to keep a distance from whoever does not fit in their frame of ideology.

“We would go to the extent of immolating ourselves before Parliament if the government makes any move or accepts any proposal to confer the Bharat Ratna on the Dalai Lama,” Ven. Bhikkhu Ananda Bhante, the General Secretary of the Maha Bodhi Society in Bangalore, told reporters back in the 2000s. Though these Theravada Buddhist societies in India are relatively small, many other minor Indian religious leaders are, perhaps, concerned that the unmatched eminence and charisma of the Dalai Lama may overshadow their presence and reduce their own influence. The Indian government, somehow, I think, correctly understands this dilemma and does not want to hurt their sentiments. It is because unlike in other countries, religious conflict in India is very complex and dangerous. India’s weakest point is religious conflicts. Each of the religious leaders in India has millions of followers; thus, the government and political parties are very cautious about taking any measures against the interests of the religious communities.

From 1954 to 2019, the Indian government conferred 48 Bharat Ratna awards. The recipients were primarily politicians and freedom fighters, and have included two foreign recipients, Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Nelson Mandela, and one naturalised citizen, Mother Teresa. However, the government has never conferred the award on any religious leader. Perhaps, this is an unwritten principle behind the award. India is a country with many famous religious leaders; each one of them has an active and emotionally attached community of followers. So, it is dangerous to bring them into this awarding competition. It will be like playing with fire. The process of selecting the Bharat Ratna recipients has always been controversial and political, from its very beginning in 1954. It has even been forced to suspend twice in its history. Besides, the award to the late Subhas Chandra Boss was legally challenged and subsequently cancelled, and CNR Rao’s award was challenged by his fellow academics, including prominent figures Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai. They even filed a legal case of plagiarism regarding CNR Rao’s works. There have been many such cases. Thus, perhaps, the government prefers to avoid such problems before they can occur.

—

* Kunsang Thokmay is a PhD student of Oriental Studies at Oxford university and also works as an assistant researcher at the university’s Socio-legal studies.