By Dr B Tsering*

By Dr B Tsering*

Introduction

An early and tactful advent of schools for Tibetan children in-exile is at the heart of Tibetan refugees’ success story. Considerable improvements have been made in education resources (both human and material) under the leadership of the Department of Education (DoE), Central Tibetan Administration (CTA). An effective school leadership provides resources and initiatives that encourage equitable access to education, including initiatives focused on creating safe and supportive learning environments, providing professional learning for teachers, and helping students develop 21st century learning skills (Hornung & Yoder, 2014; Institute of Educational Leadership IEL, 2001). Over the last 58 years, the education landscape of the exile Tibetan community has changed dramatically calling for urgent structural, functional and cultural changes in the system. It is an excellent opportunity to assess the progress that has been made and identify where challenges persist. This paper hopes to contribute to the DoE’s school improvement initiative by offering intervention strategies that are based on best practices, performance management, and collaborative leadership that will ferment a continuous cycle of self-evaluation and improvement, both at the individual level as well as institutionally.

Analysis: Past to Present

The first Tibetan school was started in 1960 in Mussoorie with 50 students with a dual goal of imparting high-quality modern education and teaching Tibetan language and culture to Tibetan students (DoE, 2018). According to the DoE website, it now oversees 73 Tibetan schools – excluding the pre-primary sections and private schools – in India and Nepal comprising around 24,000 students and 2,200 staff members. The schools are run by five different school administrations: Central Tibetan Schools Administration, Tibetan Children’s Villages, Tibetan Homes Foundation, Sambhota Tibetan Schools Society, and Snow Lion Foundation. According to the Tibetan demographic survey published by CTA in 2010, the effective literacy rate of the exile community is at an impressive 82.4% (CTA, 2018). Despite miraculous past achievements, a general sense of dissatisfaction and a growing number of new challenges – some of which were of serious nature – began to surface during the last two decades (DoE, 2018). In 1998, a six-member National Education Policy Drafting Committee carried out an internal survey of the schools that resulted in the publication of a Current Status Report (CSR). The areas of concern highlighted by the CSR were:

- The overall academic standard in the schools is not satisfactory.

- Declining standard of Tibetan language in the schools.

- Students lagging behind in their performance in science and math.

- Declining number of boys entering higher education.

- Shortage of [high quality] teachers.

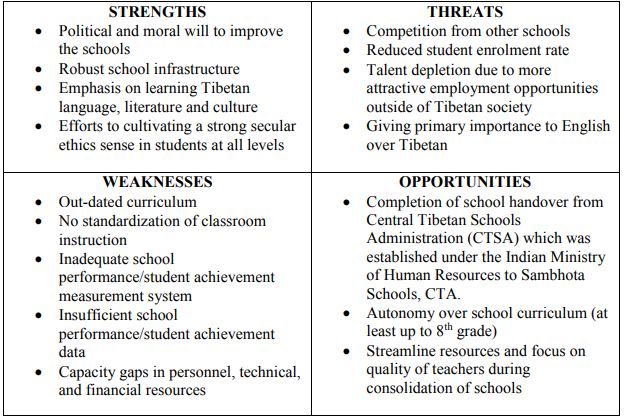

As a long-term measure against those challenges, the CTA framed a ‘Basic Education Policy’ in 2004 for implementation by the Department of Education and different school bodies but the Tibetan school systems continue to face quality of education issues, shortage of effective teachers and leaders, unsatisfactory Tibetan language standard and decline in student enrolment rate in the schools. Past efforts and initiatives have brought highly valuable insights for leaders and practitioners. With challenges, comes opportunities and mobilizing the cumulative knowledge and resources in a strategic manner can make high-impact, tangible differences for students. A SWOT table (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities & threats) highlighting the internal strengths and weaknesses of the Tibetan school system, along with some external threats and opportunities are presented below.

Table 1. SWOT Analysis

School Support and Interventions

1. Teacher Evaluation System: Lack of effective teachers is a chronic issue facing the school system. Over the years, the DoE and school administrations have made the efforts to transform teachers’ classroom practice primarily through [offsite] training workshops (DoE, 2018). However, these efforts have had limited success. One potential reason for its limited success could be because a one-size-fits-all workshop/training approach restricts viewing “teachers as individual professionals with their own strengths and weaknesses” (McGuinn, 2015) making individualized, specific information about performance especially scarce in the teaching profession. Thus, a lack of information on how to improve could be a substantial barrier to individual improvement among teachers (Taylor & Tyler, 2012).

A practicebased assessment that relies on multiple, highly-structured classroom observations conducted by trained evaluators (who could be a peer teacher) and administrators help in several ways. “Teachers learn new information about their own performance during evaluation and subsequently develop new skills. New information is potentially created by the formal scoring and feedback routines of Teacher Evaluation System (TES), as well as increased opportunities for self-reflection and for conversations regarding effective teaching practice in the TES environment” (Taylor & Tyler, 2012).

A well-designed TES connects all the components of quality education in a seamless manner – professional teaching standards, student learning outcomes (SLOs), curriculum development, assessment, and sharing of knowledge between teachers – so that teachers feel empowered to commit to continuous learning and improvement in their professions. . And it should create structures that make good evaluation possible: time and training for evaluators, the support for master or mentor teachers to provide needed expertise and assistance, and high-quality, accessible learning opportunities [like workshops, in-service, trainings] supporting effectiveness for all teachers at every stage of their careers (DarlingHammond, 2014). Training of evaluators is the single most important task in the implementation of the [new] teacher evaluation system(s) (McGuinn, 2015) and thus, leadership has to think carefully about reallocating resources and prioritizing adding or re-assigning staff to manage the teacher-evaluation work. School principals and administrators should also go through the evaluation training together as a cohort.

A mammoth cultural shift – and not just within the education community – is to change the perceptions around the purpose of the TES. It is necessary to move the conversation from the punitive – focusing on getting rid of a small number of bad teachers – to the productive – using better information to improve the instruction of all teachers and creating a continuous improvement model (Fagnanl, 2014). It cannot be emphasized enough that the purpose of the TES is not to adopt “an individualistic, competitive approach to ranking and sorting teachers that undermines the growth of learning communities” (Darling-Hammond) but to ultimately create a collaborative learning environment where “teachers are more engaged with each other to leverage strengths and address challenges made visible through the TES” (McGuinn, 2015). Research shows that student gains are most pronounced where teachers have greater longevity and work as a team (Bruegmann & Jackson, 2009).

2. Leader Evaluation System: Strong professional learning communities require “leadership that promote student learning through their ability to provide instructional leadership support, plan strategically, communicate with all constituents, collaborate effectively with staff, implement board policy, manage financial and human resources, and set the academic tone for the [school]” (Callan & Levinson, 2010). There is no doubt that school leaders at all levels wear many hats, constantly juggling multiple roles and responsibilities. Thus, developing ‘a framework for leadership’ that sets performance standards at each leadership position is vital. Performance standards articulate expectations for leaders in clear language that can be assessed using multiple measures (Hornung & Yoder, 2014).This process can also spur a redefinition of existing school leadership roles and reallocating some responsibilities or providing additional support where needed.

School leadership provides a critical bridge between most education reform initiatives, and having those reforms make a genuine difference for students (Leithwood, et al., 2004). Evaluating [school] leaders strengthens the comprehensiveness of the [TES] and provides [school] leaders with opportunities for evidence-based feedback and recognition (Hornung & Yoder, 2014). It is crucial that school Leader Evaluation System (LES) “be aligned with the new TES to ensure that [school] leaders are appropriately incentivized to assess and coach teachers with rigor and objectivity” (Schuerman, et al., 2014).

3. Curriculum Standards: Figuring out how to meaningfully measure student achievement or growth in their classrooms in a given school year has piqued educators worldwide. Tibetan schools exercise a considerable degree of freedom in designing their own curriculum especially at the elementary level. Getting practitioners talking about measuring: measuring academic performance, measuring the growth of their students, using data to inform the discussion to determine what sort of outcomes they want to see brings [an] inherent benefit (McGuinn, 2015) of the teaching process. Therefore, curriculums at all levels should be based on objective, reliable and comparable student learning objectives (SLOs) or student growth objectives (SGOs) designed by teachers in partnership with administrators. SGOs should be student-focused, teacher-driven and administrator-supported (McGuinn, 2015). This would be a new task for many teachers as well as administrators, and will require a lot of support and training.

Precise and well-calibrated SLOs demand that schools create “curriculum-embedded assessments that are reflective of what has been taught and that really push students to do problem solving and higher level, more rigorous work as a way to measure their own growth and learning of the curriculum and also to inform SLOs” (McGuinn, 2015). Student growth results then feedback into TES and LES to inform decisions about educator placement, retention and professional development.

4. Centralized Data Collection and Reporting Systems: Identifying trends in student performance allows for data-driven, early detection support system (Missourie Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2016). A crucial piece of the new evaluation systems is the data collection and reporting systems that [schools] and [DoE] will use to gather, analyze, and disseminate the information. Data, at minimum should include – at an aggregate and individual level – student achievement results, teacher and [leader] evaluations, school-level administrative data, and analysis of the curriculum to align with SLOs. To ensure that the new evaluation systems function as designed and generate reliable, high-quality data and how to use the new information that is gathered to better guide personnel decisions and instructional improvement is crucial to the long-term impact of the [new] system (McGuinn, 2015).

Center for Academic Excellence

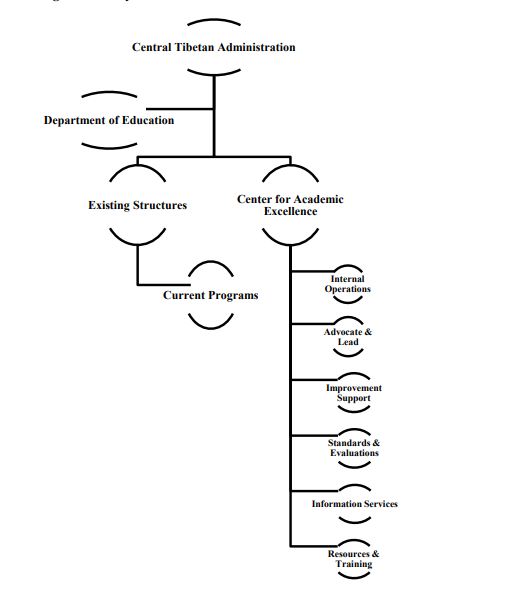

Given the enormous importance and complexity of school reform initiative(s), it is important to reorganize education agencies around discrete functions that can integrate the new roles and responsibilities (McGuinn, 2015). Thus, to bring about valid, accurate and meaningful changes in Tibetan schools, a new intermediary structure is needed. It is worthwhile to note that a similar recommendation was proposed by the Basic Education Policy Drafting Committee in 2004. Establishing a service delivery/school improvement organization such as a Center for Academic Excellence (CAE) under the DoE will enable direct and intensive support for the schools during the process. The resources, information, and assistance provided by the CAE will constitute the value added for schools to ensure that each and every student is prepared for college and career in an increasingly competitive world. Of course, the CAE fulfills its purpose within the CTA’s DoE framework and the Tibetan context.

The set of functions proposed for the CAE are:

- Provide leadership and advocacy.

- Provide information.

- Set standards and evaluate teachers, leaders and curriculums.

- Provide resources and training.

- Assist with continuous improvement.

These functions provide the building blocks for the organizational structure of the CAE. Deploying these functions to achieve a coherent structure demands establishing clear purposes, boundaries and responsibilities for each functional area (Redding & Nafziger, 2013).

Provide leadership and advocacy – The head of the CAE sets a vision for the organization and communicates that with the public. By identifying, assessing, and analyzing trends in Tibetan education as well as education field at large, CAE advocates on behalf of children, parents and educators for excellence in all the schools. When rolling out new education initiatives, the CAE will determine implementation timetables and sequencing of evaluations.

Provide information – The CAE is responsible for gathering, organizing, and presenting information for internal and external purposes. Information includes research, reports, practice guides, and management of the centralized data system. The CAE constantly monitors evaluation results on the back-end, looking for misalignments based on teacher observational scores and student achievement data.

Sets standards and conducts evaluations – The CAE helps determine requirements for education professionals and based on best available evidence sets standards for what students should know and be able to do at key points in their education. The CAE will ensure accountability through ongoing performance evaluation programs and feedback systems.

Provide resources and training – The CAE allocates resources in skills, expertise, and services to the schools. It brings educators together as well as those in non-teaching roles but provides critical services in schools to develop the evaluation instruments, how the instruments could apply to their specific roles and functions and a set of guiding questions that could support their supervising administrators (McGuinn, 2015). Engaging stakeholders and practitioners in the field right from the planning phase is crucial so that “everyone develops shared standards of practice and a collective perspective on how to improve the work” (Darling-Hammond, 2014). The CAE also carries out the vital function to train the evaluators adopting a model of training them directly or train-the-trainer model or a combination of the two.

Assist with continuous improvement – To adequately support improvement, the [CAE] provides schools with processes and tools for diagnosing current practice and outcomes, planning their improvement, and implementing and monitoring their plans (Redding & Nafziger, 2013). It allows time and resources for collaborative planning creating productive working relationships between the schools, within academic departments, and among teachers so that it stimulates knowledge sharing about best practices from the field to improve outcomes in schools.

The CAE should be structured around these functions and then appoint personnel with the requisite skills and expertise within each functional categories. An organizational structure for CAE adapted from Redding and Nafziger’s (2013) example of a structure of State Education Agency is illustrated below.

Figure 1. CAE Organization by Function

Conclusion

Tibetan schools are unique and have much to offer, not just to the Tibetan society but to all modern societies. The distinct combination of modern education with traditional Tibetan values and language provides students with not just academic achievement, but holistic growth and development. Tibetan leaders and educators have stood the test of time and history by staying committed to providing high-quality education to the children they serve. Tens of thousands of refugee children’s lives have been changed because of the education they received from the Tibetan schools.

It is a critical moment in school reform for the Tibetan exile community. Some long-standing educational issues have been exacerbated with changes in demographics, increasing competition, brain drain etc. The strategies presented in this paper are not intended to serve as means to an end, but rather as a much-needed step toward stimulating educators’ collective learning. The new knowledge that will emerge from these measures can help tailor professional development and learning goals; more importantly it can help build a strong teacher education system so that educators are well-prepared even before they enter the profession.

A common refrain from the field is the need to set realistic expectations around the new [educator] evaluation systems – both in the sense that people realize that it is complicated, difficult work during which mistakes will be made and also that getting the new systems operating smoothly and effectively will take several years (McGuinn, 2015). Picking few schools and piloting the new system will help identify and resolve any problems that emerge and give educators time to adjust to the new system and their roles within it.

* About the Author

B. Tsering is the Principal of the Dalai Lama Institute for Higher Education in Bengaluru, India. She holds a Ph.D in Education and M.Ed.in Social Foundations in Education from University of Virginia, Charlottesville. In 1998, she was awarded the Margaret McNamara Education Grant. She was a visiting fellow at National Endowment for Democracy in Washington, DC in 2012 where she did a seminal work looking at gender gap in leadership roles in Tibetan exile community. She has 20 years of teaching experience and also held administrative positions at Tibetan Children´s Village, Dharamsala. She was one of the members of CTA`s Basic Education Policy Drafting Committee in 2004.

References

Callan, M., & Levinson, W. (2010). Achieving success for new and aspiring superintendents: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Central Tibetan Administration, 2018. Title of the Page. [About CTA]. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/about-cta/tibet-in-exile/

Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). One piece of the whole. Teacher evaluation as part of a comprehensive system for teaching and learning. American Educator. Spring Ed., 4-13.

Department of Education. (2018). Title of the page. [Department of Education]. Retrieved from http://tibet.net/department/education/

Department of Education. (1998). Current Status Report. Dharamsala:Department of Education Publication.

Fagnanl, S. (2014). Drilling down on education data. District Administration. Retrieved from http://www.districtadministration.com/article/drilling-down-education-data

Hornung, K., & Yoder, N. (2014, May). What do effective district leaders do? Strategies for evaluating district leadership. Washington, DC: Center on Great Teachers and Leaders at American Institutes for Research. Policy Snapshot, 1-10.

Institute of Educational Leadership. (2001). Leadership for student learning: Restructuring school district leadership. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.iel.org/programs/21st/reports/district.pdf

McGuinn, P. (2015). Evaluating Progress: State Education Agencies and the Implementation of New Teacher Evaluation Systems. White Paper (#WP2015-09). Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Schuerman, P., Goldring, E., Cannata, M., Drake, T., Grisson, J., Neumerski, C., & Rubin, M. (2014). Supporting principals to use teacher effectiveness data for talent management decisions. Retrieved from https://westcompcenter.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/Supporting-Principals-to-Use-Data-for-Talent-ManagementVanderbilt.pdf

Taylor, E., & Tyler, J. (2012). Can teacher evaluation improve teaching? Education Next. Fall Ed., 78-84.