Debutant novelist Tsering Namgyal Khortsa* reflects on the challenges, joy, and lessons learnt in taking up fiction-writing as a Tibetan exile.

(TibetanReview.net, Mar02’20)

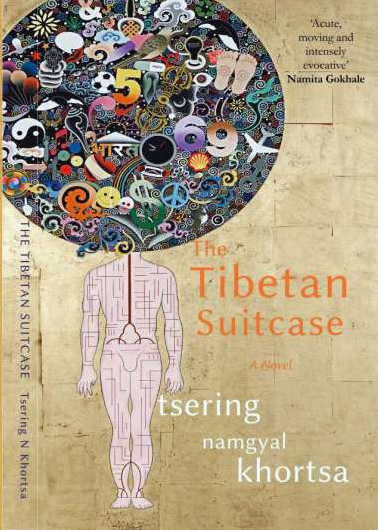

Last November I did something rather bold. I published a novel in English titled The Tibetan Suitcase, which is the first book-length work of fiction published by a Tibetan born in India. I believe that we need more stories about present-day Tibetan lives. As 2018 Nobel Literature Laureate Olga Tokarczuk said in her Nobel Lecture, societies without stories cease to exist and, by that logic, societies that have been deterritorialized are particularly susceptible to meeting this fate.

It was with this vision that I wanted to write the book, and I chose fiction as my preferred form because I wanted to turn away from journalism and non-fiction to do something more artistic and innovative.

I had, however, underestimated the challenges of writing a full-length novel, especially one that is set in the Tibetan community, and the road to publication was not as smooth as I had expected. I published the novel as an e-book in 2013 in the US, hoping that I would bring out a print edition later. And while I was looking for publishers in India, I found the time to add an ending and a beginning to make the narrative more complete.

I am happy to hear from my readers who tell me that they love the book, and find the story not only very moving but an accurate depiction of our peripatetic condition. Some readers also told me that the ending was not convincing and that I should have left the book somehow open-ended and also that it should have ended in the voice of the protagonist. I decided that the fact that readers feel so emotionally invested in the book is definitely a good sign.

Like most first novels, the book is partly autobiographical. Most of it, however, is purely made up (I was not born in Dharamshala, and I did not even attend university in Delhi, and ironically, I have never fallen in love with a girl in an American university.)

Let me add a few words on why there is a main character who is a student of creative writing. The most common question that people ask me, with a tone of mild disbelief, when I say that I have written a novel is: “Is it in English?” This perhaps shows that a novel – by which I mean a European novel – as a form is so new in the Tibetan context.

To convince my readers, I show them the process of how it is being written, lock stock and barrel. Readers will see how the protagonist is not only reflecting on the dearth of Tibetan fiction but also learning how to write a so-called “Tibetan novel in English” in the novel (it is a bit like an introduction or a user’s manual embedded in the very book they are reading.)

Many readers are also quite flabbergasted by my style because I broke so many rules. And the great thing about the novel as a form is that it pushes the author to break the rules so that it is “novel” or new.

My book is also made up of bricolage of letters, application letters, journal entries and newspaper articles.

When I was growing up, we did not have telephones, let alone the internet. Writing the book allowed me to reimagine those days when one waited with bated breath for the news from your loved ones. Writing the book also allowed me to relive the languorous pace of those days (and recover some of the lost time in a very Proustian sense.)

The Tibetan Suitcase, which includes a variety of different texts, stands as a testament to the novel’s flexibility as a form. It shows how a novel is perhaps the only literary form that retains its nature irrespective of whatever you put into it (I am paraphrasing the great Russian scholar of novel Mikhail Bakhtin).

I decided to write most of it in letters for several reasons. For one, it was the best way of writing about long-distance relationships (in our case, often, long-distance nationalism). Secondly, I realized that writing letters to imaginary beings were, for better or worse, something I was quite good at.

The discovery of the epistolary style, therefore, was a major technical breakthrough for me. I feel this style worked in the context of the narrative of a diasporic community scattered around the world, and especially suited for the material I was working with.

I believe many Tibetan writers are facing similar challenges. And some of them have found their metier. For example, I admired Pema Tseden’s short story The Dreams of a Wandering Minstrel translated by Tenzin Dickie. It was beautifully told and was very conscious of its form; I suppose it has a lot to do with his background in cinema. I have also heard great things about Tashi Dawa and Alia and am planning to read and study their work soon.

There are also many fine writers in English outside Tibet. I am in awe of Jamyang Norbu, Thubten Samphel and late Dr. Tshewang Pemba, whose work I read and respect. I am eagerly looking forward to Thubten Samphel’s upcoming novel, his second work of fiction, as well as late Tsering Wangyal novel which is in the pipeline.

There are also great writers of non-fiction in the Tibetan community that I admire such as late Dawa Norbu, late K Dhondup, late Dhondup Gyal, Tsering Shakya, Tenzing Sonam, Tenzin Tsundue and Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, and many others. Most importantly, there are also many distinguished poets and writers who work in the Tibetan language in a thriving literary scene.

I must applaud recent efforts by writers like Bhuchung D Sonam (the publisher of Blackneck Books) and Tenzin Dickie (editor of Old Demon, New Deities: 21 Stories from Tibet) who are working so indefatigably, and often at great personal cost, to publish Tibetan stories.

Like my illustrious predecessors, I try to not only put into words the peculiar existence of this small diaspora, but also challenge stereotypes of all kinds in my work. This includes experimenting with a new narrative technique and also writing, often irreverently, about love stories and bar fights (just as Japanese writers must have been doing for years) in the context of contemporary Tibetan lives, without trivializing Buddhism’s rich history.

Ideally, the themes of exile, diaspora, language, identity, and migration seem like perfect material for fiction. I even go so far as to question if traditional fiction – what Milan Kundera calls as the “European novel” – is actually the right form to tell the story of Tibet at this moment. Or should Tibetan authors, because we have collectively suffered so much, only write “trauma literature”? This is a different topic altogether.

I also have great respect for Tibetan scholars of the past. One of the main characters, Khenchen Sangpo, is a composite of some of them. Rather than turning away from this great legacy, I chose to take inspiration from their lives as I write for the readers in the present and future moments. That said, this is a work of art and the characters and their backgrounds are merely symbols of larger truths.

Writing literary fiction, I believe, is essentially a struggle to find the truth. The author sets off in his mission in a very Buddhist way. The art of fiction allows the writer to explore truths such as the lack of a fixed and permanent self, and that everything is possible, as long as causes and conditions are met. The author comes to these realizations as he struggles to make his imaginative vision objectively believable, or even inevitable, through the sheer force of the narrative and the power of the author’s logic.

Ultimately, I think my characters realize in the end that while each of us is pursuing our dreams as if life is a linear trajectory, we tend to forget that the journey is ultimately spiritual. And, at the end of the day, we all long to return to our roots.

But it’s not easy being a Tibetan writer. There are days you feel like giving up writing. That would be quite selfish because books can have an amazing impact on people’s lives.

One of my last reviewers happened to be going through personal trauma when she read the book. Reading the book, she thought, was a therapeutic experience for her and that she complimented me on how well I have managed to integrate Buddhist teachings into my narrative. I was happy to hear it because that is what all fiction aspires to do in the end, which is to heal the reader.

That alone is the reason why one should write: that one person whose life you might end up saving.

Unfortunately, we, as stateless people, are homeless in terms of literature. For this reason, we should write our stories all the more, and it is a matter of great pride that the Gesar Epic is known as the longest in the world. So we are not starting from scratch.

Having said that, we must tell these contemporary stories in a way that readers can understand and enjoy. The issue of language and translation is something quite dear to me. One question that I often ask is what kind of language (in this case English) should I use to tell the stories about Tibetan diaspora. I did not set out to create a specific language for the book, but you will hear uncommon cadences and drawls of Tibetan-English in the book (including some Babu English). This is especially true because the novel is written entirely in the voices of the characters. There is no narrator and a lot of what the author is doing is translating Tibetan stories in contemporary English.

It may not be perfect, but someone has to do it. After all, the book is about paving the path for the other writers, showing them that it can be done by helping them imagine the possibilities in Tibetan storytelling.

I just wanted to set an example.

The publication of this novel should be seen as an important milestone in the ongoing revival of Tibetan literature so that we no longer are as Tenzin Dickie so aptly put it “literary orphans.” Echoing Tokarczuk’s statement about societies without stories, we that we can keep calling ourselves “Tibetans” as long as we have Tibetan stories being published. I owe this book to the community that has given me so much.

—

* Born in India, Tsering Namgyal Khortsa has pursued journalism in Taiwan and the United States and holds degrees from the National Taiwan University, the University of Iowa and the University of Minnesota. His articles have appeared in some of the leading publications in the Asian region, including the South China Morning Post, the Asia Sentinel, Asia Times, Himal Southasia, India Today and Global Asia. His short fiction has appeared in Yellow Medicine Review: The Journal of Indigenous Culture Arts and Literature. One of his short stories has been anthologized in Old Demons, New Deities: 21 Short Stories from Tibet (Edited by Tenzin Dickie) published by Or Books in the US and Navayana Books in India. He is the author of two previous books, Little Lhasa: Reflections of Exiled Tibet (Indus Source Mumbai) and His Holiness the 17th Karmapa: A Biography (Hay House India.) and The Tibetan Suitcase: A Novel (November2019)