Hemant Adlakha, Associate Professor and Chairperson, Centre for Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Looks at the Tibet issue as a part of his study on China, his field of specialization, refers to the Tibet-related policies and actions of former party General Secretary Hu Yaobang and former President Hu Jintao to draw the conclusion that China and Chinese leaders only use the Tibet issue as a game to attain their goals without ever intending to solve it.

This article appeared in the Special Issue 2018 edition of the Tibetan Review, published in association with the JNU Tibet Forum at the 2nd annual symposium in memory of Prof. Dawa Norbu organized on April 7, 2016.

———————————————

ABSTRACT

In 2015, at a commemorative meeting on the 100th birth anniversary of Comrade Hu Yaobang in the Great Hall of the People – the first such official and public celebration of the Long March veteran in nearly thirty years since his removal as the Party general secretary in 1987 – Mr Xi Jinping, flagged by all the other members of the CPCCC PBSC, praised his predecessor as a reformist leader who devoted his entire life ‘to the party and the people’.

While calling Hu Yaobang a communist pioneer whose achievements in socialism with Chinese characteristics were immortal, Mr Xi, the conservative hardliner, was conspicuous in deliberately leaving out references to Mr Hu’s many liberal views, including what is still hailed by Tibetans as the Party’s former Tibet Work Forum chief’s bold and unorthodox approach in championing the cause of Tibet.

Last year was also the 36th and the 65th anniversaries of Hu Yaobang’s association with Tibet in the political annals of the party history. Following four unyielding fact-finding teams the Dalai Lama sent to Beijing, apparently at the initiative of the then party general secretary and following the rejection of His Five-Point Peace Plan for Tibet (soon after the dismissal of Hu Yaobang) in September 1987, His Holiness is reported to have said an amicable solution to the Tibet question would have been in sight had Hu Yaobang lived for some years.

Not unsurprisingly, skeptics in Beijing and in Lhasa have cast doubts on party’s sincerity in commemorating the fallen leader. A prominent Tibetan poet has called the celebration as a PR exercise with no positive bearings. “It’s like the fox borrowing the dead sheep’s skin to hunt more of the gullible animal.” Yet, the centenary celebrations of the much loved champion of ‘all Chinese people’ has given hope to liberals within the CPC and inside the PRC – ethnic Hans, Tibetans and people of other minorities – that the current general secretary, out of personal reasons or out of political factors, might be willing to bring the legacy of sku-zhabs Hu (‘Gentleman Hu’, a term Tibetans affectionately use to refer to Hu yaobang) out of shadows.

————————————————————————–

Like my fellow co-panelists, let me also begin by thanking the Tibet Forum and the organizers for giving me this opportunity. It is a wonderful mission to remember Professor Dawa Norbu. I will not repeat what I had said about my friendship and my association with Professor Dawa Norbu at the first symposium which was held last year.

Let me also clarify, unlike my co-panelists, I am neither a Tibet scholar nor a Tibet specialist. I look at the Tibet issue as part of my ongoing research and study on China and Chinese politics. I have decided to speak on a single issue to share with you my attempt to understand how the Chinese Communist Party’s thinking on Tibet has been evolving or has been shaping up. It is with that in mind that I have chosen the topic, which has been circulated to you along with the abstract.

Last year, the Communist Party of China (CPC) honoured the ‘disgraced’ former party General Secretary Hu Yaobang for the first time since his death in 1989. The occasion was the CPC officially holding celebrations to remember the Long March veteran on his 100th birth anniversary. The current Chinese President and the party General Secretary Xi Jinping too attended the celebrations, along with all the other six CPCCC Politburo Standing Committee members. More than the foreign media and the observers abroad, the officially controlled domestic media and the social media within the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC), noted and highlighted the significance of the CPC marking the hundredth anniversary of the former Communist Youth League (CYL) leader. What was very interesting and even more surprising was the speech President Xi and others gave during the celebrations, which took place in November last year. In the speeches, Comrade Hu Yaobang was fondly remembered and all the speakers eulogized his contributions to the Chinese Revolution, to China’s economic reforms, and so on. However, no one said anything at all about Hu’s approach to Tibet and to the Tibet Question when he visited Lhasa in 1980. To an astute observer of China’s political discourse, the conspicuous absence of any reference to Hu Yaobang’s thinking on the Tibet issue raises several questions and conveys a lot of meanings.

One obvious reason for leaving Tibet out of remembering Hu’s long list of contributions is, perhaps the CPC has never been really serious about resolving the Tibet issue. Or, in other words Beijing never took seriously the then party general secretary Hu’s serious attempt to initiate a serious dialogue on the Tibet Question within the party. Dr Anand mentioned a little while ago, of course, that China now calls Tibet one of its “core” issues. The ground reality remains, I think, that Tibet is one issue which the CPC leadership uses merely as a game or political pawn. One of the best examples of this was the rise of Hu Jintao, who rose to become the party General Secretary and the President of the PRC in 2002 and 2003, respectively.

Literature now publicly available within the PRC clearly shows how he used his Tibet ‘card’ to rise up to the highest position in the CPC political hierarchy. Before becoming China’s top leader, he was known to be a young leader with liberal outlook, with Hu Yaobang as his mentor.

Hu Yaobang is still remembered as a very distinctly different leader from all the other party leaders because of the kind of changes he promised to bring about and also initiated until he was removed n 1987 for being too liberal. He tried his best to introduce lots of things which were not even thought of before. And he was given the task in the party to look after the Tibet Policy.

With this background, I thought it a very good exercise to try and understand why the party suddenly decided, after 30 years, to remember him. And when the party chose to remember him, it completely ignored the contributions he initiated towards Tibet.

As I told you at the beginning of my talk, I am not actually a Tibet scholar. But thinking of the topics for the symposium, ‘Tibet, China and the global politics’, I remember a very important observation made by a Chinese intellectual who is, I think, the best known one outside China at present. I am referring to Wang Hui. When it comes to the issue of Tibet, he recently observed that it is a very peculiar situation for Chinese scholars or Chinese students when they first arrive in a foreign country, especially in Europe and America. They are, for the first time, confronted by the reality that the Tibet issue is never being clubbed with the China issue in the outside world. That comes as a shock to them and also confuses them because within China the Tibet issue is never discussed or taken up as something which is not Chinese or not a part of China.

So, within China there is no Tibet issue as such. But outside China the situation is completely different, wherever you go. This is the contribution of the struggle of the Tibetan people over the past several decades that the Tibet issue has come to be treated like no other parts of China inhabited by other ethnic minorities. So, that is one thing in the context of China and global politics with regard to the Tibet issue.

Now, I will quickly read out parts from what I have prepared for today’s Symposium. Towards the end of the presentation, I will conclude by quoting again more observations from Wang Hui, because he has also written a very important, very long article on the Tibet issue in Chinese and that is published in China. Of course, many among you must have seen the article. I don’t know whether or not the full article is available in English translation. I met Wang Hui soon after he wrote and published his article and I asked him whether he did not face any problem for publishing it in China. He replied “yes” but continued that the fact that one faces problems does not mean that one would stop writing.

Following the passing away of Mao Zedong in 1976, and the emergence of Deng Xiaoping as China’s top leader a couple of years later, the CPC chose the Long March veteran and the then General Secretary of the party, Comrade Hu Yaobang, to go to Lhasa. On his maiden visit Hu announced “corrective” measures in the country’s Tibet policy – the first such announcement since 1949 or during the Mao period. It is significant that the CPC separated Tibet from other minorities and it approached the Tibet issue in the new domestic political situation as not a part of the existing minority nationalities policy China was practicing at that time. Hu Yaobang was accompanied by Wan Li, another veteran party leader and a vice premier of China at that time. There were two other leaders in the five-member delegation, but they are not mentioned in the Chinese literature.

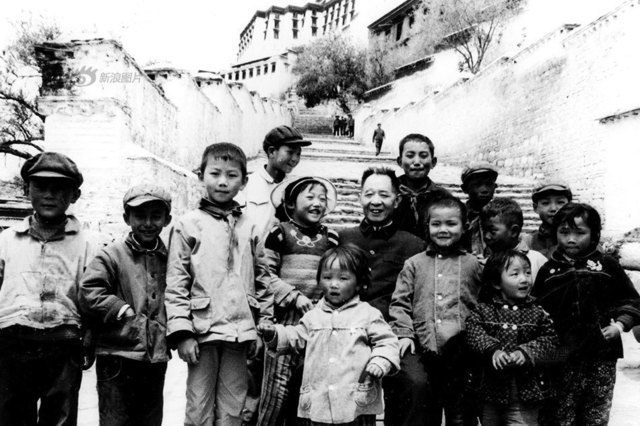

However, I recently did see a picture of the two other younger leaders who had got themselves photographed with Hu Yaobang in Lhasa at the time. But their names are not mentioned anywhere in literature. They were also part of the trip and they both went on to become important leaders of the CPC in the future. One, of course, was Hu Jintao, who, as I just mentioned, used the Tibet issue to rise up in the party politics. The other leader who was with Hu Yaobang was Wen Jiabao, the premier who served under Hu Jintao.

Anyway, Hu Yaobang and the other leaders who accompanied him then announced that the hard-line approach of the CPC towards Tibet thus far had been an absolute failure. Hu therefore introduced some new policy measures which have since then been recognized or accepted (within the CPC political discourse) as “softening” of China’s approach towards Tibet.

The reason why I am raising this issue here is because when I look at the Chinese literature on the Tibet Question, when I look at the Chinese debates, there is no mention of Hu Yaobang’s announcement of new policies for Tibet during his Lhasa visit in 1980. This raises the question whether the policies he announced and tried to implement had been even discussed in the party? Was that ever documented as the party decision either in the Central Committee leadership or in the Politburo? We know that the Communist Party of China, like other communist parties, does not function without documentation, without the decision being adopted at the Central Committee, especially when it comes to major decisions. It is therefore a mystery to me whether the new Tibet policies Hu Yaobang announced in 1980 were his own initiative or whether that was the party decision. What was the task given to Hu Yaobang with regard to China’s policy towards Tibet at that time?

It is very interesting that Hu Yaobang was removed in 1987 on the charges of being too liberal, according to at least a couple of commentaries and articles in Chinese that I could access. These commentaries very clearly observed that one of the main reasons why Hu Yaobang was removed was not because he had a very liberal approach. Rather, he was removed because he went from far ‘too left’ during Mao’s period to far ‘too right’ on the Tibet issue. I mean, this was cited as one of the main reasons for his removal, he went far too right when it came to the issue of Tibet. This is very interesting indeed.

A couple of questions arise here. One is concerned with the new CPC regime’s changing attitude towards minority nationalities in general, specifically on the Tibetan minority. Remember the six-point programme for Tibet initiated by Hu Yaobang which is always seen in comparison with the 17-point agreement of 1951. Hu Yaobang had very clearly mentioned that ‘cherishing the people of minority nationalities’ is not an empty talk. There has been no other top Chinese leader, especially a party general secretary, who had said or used this kind of language about non-Han nationalities in the People’s Republic of China.

Was the six-point reform programme or package discussed at a Standing Committee meeting of the CPC politburo? We don’t know yet. Or, was it just a fragile attempt to undo the damage caused by the Great Proletarian Culture Revolution (GPCR) during the Mao era in Tibet? Finding an answer to this question is not easy.

But even if one attempts to link them to construct a plausible answer, there is another significant turn of events related to Tibet in the mid-1980’s which comes to mind. By this, I am referring to Hu Jintao’s use of Tibet as a ‘game’ to make his career out of it.

As I have already mentioned, Hu Jintao, the future party general secretary, was, in the early eighties, seen as a young liberal face of the leadership. He was said to have become highly ambitious by the mid-1980’s, with the image of being a liberal. But he surprised everyone, especially the old guard leadership of the party in Beijing. It is very interesting that the old guard leadership of the party in Tibet was referred to, in the Chinese language, as ‘Jiui Xizang 旧西藏’, which literally means ‘old Tibet’. Hu Jintao surprised both Hu Yaobang himself and the entire old guard in Beijing when he used his iron gloves approach to crush the protesting Tibetans in Lhasa after the 1987-89 “riots”.

Wang Hui has made another observation on the martial law which was imposed by Hu Jintao in Tibet. Hu Jintao called the martial law “san ba 三八”, which in Chinese previously referred to 8th March for the International Women’s Day. But thanks to Hu Jintao, 三八has since came to be referred to something else, i e, the date of the imposition of martial law in Tibet. Even Ma Lin, the official Chinese biographer of Hu Jintao, has mentioned that it was the way he (Hu Jintao) handled Tibet with ruthlessness which earned him the post of the party General Secretary and the country’s top leadership posts few years later.

Two things changed the future course of the liberal or soft power approach towards Tibet in Beijing in the post-1989 period. One was the Dalai Lama’s criticism of Beijing. Though several western nations also criticized the martial law and the killings, but Deng Xiaoping took personally the Dalai Lama’s criticism of Beijing’s Lhasa policy in 1989 (according to the NYT nearly 450 Tibetans had perished during the riots; a People’s Daily write-up did publish the riots mentioning a ‘600 people march’ on 5 March 1989 in Beijing, but did not mention any death figures). This fact has been well documented by many commentators and by many scholars and writers.

Hu Yaobang had, in 1981, also prepared a five-point programme, which was shared with a visiting Tibetan delegation in 1982. This was made public in 1984. There are now questions being raised about that plan. It clearly reflected that Beijing was only interested in unconditional return to China of the Dalai Lama and did not at all show any interest to solve the Tibet issue. And I don’t think Beijing’s attitude on Tibet issue ever changed. As far as China is concerned, the Tibet problem was solved the day the CPC announced the establishment of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Now, the main problem facing the Beijing leadership was how to get the Dalai Lama back into China. Since 1989, following the death of Hu Yaobang, there has been a complete turnaround in Beijing’s attitude towards Tibet. It has now become a political game within the CPC. China now seriously believes and hopes that its ethnic minority problem will gradually disappear with the economic growth and higher living standard in all the minority areas under the current development projects and programmes.

Notwithstanding factors such as external pressure, China’s position in the world is changing in geopolitical terms as well as in economic success terms, such as the regional balance and China being continued to be perceived as the driver of the global economic growth. Beijing does not at all seem to be interested in finding a negotiated solution to the Tibet issue. It does not seem to be giving up its rigid demand of unconditional return of the Dalai Lama.