While lack of interest, lack of knowledge, disillusionment, voter apathy, and low level of political engagement may indeed be reasons for the low level of voter participation in the exile Tibetan election system, it certainly does not help that the backwardness and rigidity of the Tibetan electoral system prevents rather than facilitates the maximization of participation, writes Tenzin Sangmo* and Wangdue Tsering Kharlo*

American scholar Dr. Abraham J. Henry wrote in 1952 that “there are millions of Americans who are willing to do anything for their country but vote”. More than half a century later, this rings true of Tibetans in exile who are willing to do anything for theirs but perhaps vote.

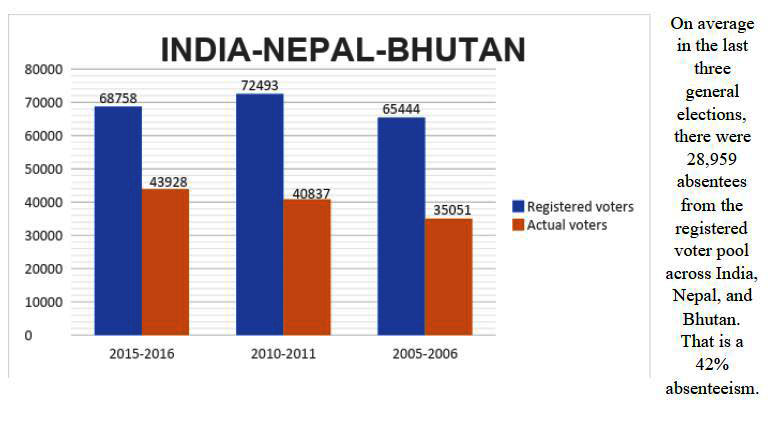

In the 2006 elections, out of 70,500 registered voters only 37,147 cast their ballots. The 2011 general elections saw 82,817 registered voters but only 48,482 votes and 2016 had 58,615 voters from an eligible pool of 90,377 registrations. The Election Commission last month announced a new window of voter registration for the upcoming election because there were 10,680 less Tibetans registered to vote than the last election. With only 79,697 registrations this time, it is a twelve percent decline. Our electoral system has remained rigid, not adopting any changes with the need of time. On an average forty-one percent of registered voters ended up not voting in the last three elections.

Our first Kalon Tripa was publicly elected in 2001. Until then the person for the position was appointed by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. This was a significant step towards achieving a complete democratic system of governance that His Holiness had long envisioned. Samdhong Rinpoche was the first democratically elected political leader who enjoyed a landslide victory. Tibetans across the world are now gearing up for the next Sikyong and 17th Member of Tibetan Parliament in Exile elections. For the first time in our history the Tibetan Election Commission launched a website in August with ‘our vote, our future’ as the mantra. Currently published in Tibetan only, it has an English section that has still not arrived.

In democracies across the world, there is always a difference between who vote and those who could vote. The last three Tibetan elections in fifteen years paint a grim picture. Voting in the Tibetan universe is as much a privilege as it is a right, a right that our brethren inside Tibet cannot enjoy. Exile Tibetans make up about two percent of the entire population. Every single person in exile owe tenfold to the ninety-eight percent inside Tibet to exercise the democratic freedom we enjoy.

The Chithue-Sikyong election of 2021 has been gaining traction and discussed quite heavily these days. With time, discourse becomes more passionate among the public. What remains to be seen is if this passion will translate into footfall to the election booth where it is required the most. With only 79,697 people registered for the 2021 election, this looks unlikely. If we emulate participation in previous elections and base it on current registration with an average forty-one percent of nonvoters,1 we will have only 47,022 votes next year.

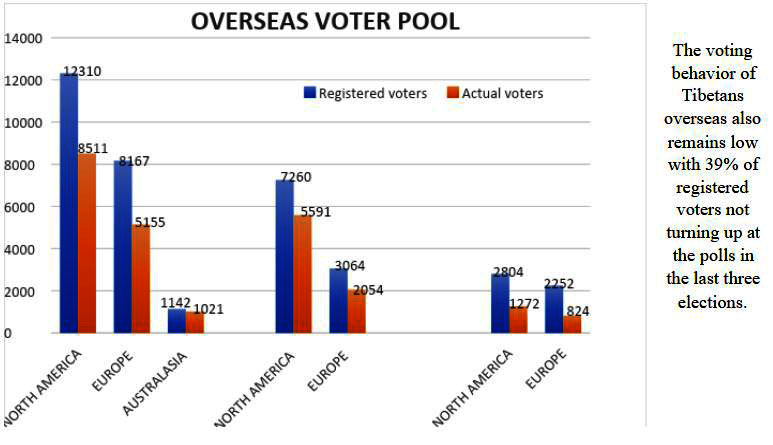

The rudimentary graphs below depict voter engagement in our elections. From the time, an ‘intended’ voter registers to vote, to the actual voting day we see a decline.

For the 2021 elections, EC recently announced there were only 24,014 registrations overseas. With 55,605 eligible registrations there is still a large 57% of Tibetans overseas that did not register.

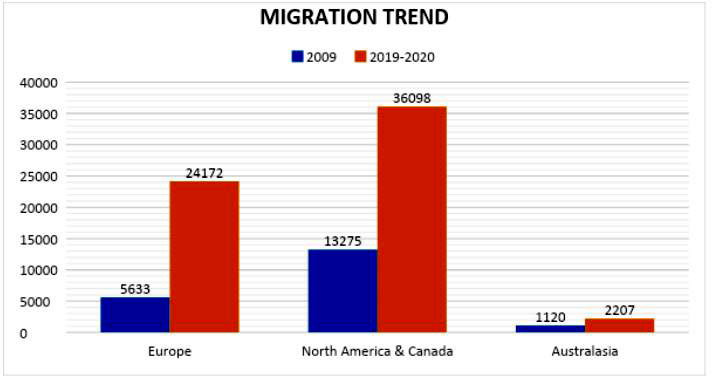

Reasons we do not vote could be lack of interest, lack of knowledge, disillusionment, voter apathy, a low level of political engagement and perhaps large part of it could be an inflexible electoral system. There are also other factors at play in a society like ours where not everything can fall under one band. The Tibetan population is an aggressive migrant, seeking greener pastures and inherently true to our basic instinct and in the real sense of the word nomads. This is evident from the increase in our population in the Americas, Europe, Australasia, and other countries.

Before voter registration is possible, one must hold a Green Book that is current with up-to-date payments at the place of current residence if 12 months or more have passed in that country. Many Tibetans who move overseas leave their green books behind and family members make payments or are ignored. Another roadblock is Tibetans either not having a green book or losing them. They do not pay their contributions or take necessary steps to rectify these and hence cannot register to vote. The Green Book remains the most important qualifier for eligibility. Digitization can pave the way to ousting the orthodox paper system and introducing online payments that can be made anywhere in the world.

Extending registration is not a solution to the problem; it is delaying the inevitable. The Election Commission must dedicate time and resources available to them for a more tangible result. A study on demography, past Tibetan elections, migration, learnings from recently conducted public survey, Covid-19 have all contributed to the need of an ‘Easy Enrol, Easy Vote’ system. It understands the complex structure of the diaspora and caters to the Tibetan population that is scattered across the globe.

Easy Enroll, Easy Vote: To encourage engagement the voter enrolment process should be easy and convenient. The new Election Commission website can make provisions for online enrolment and a toll-free number that is accessed internationally with Green Book as voter verification ID. We have a staggering 94% literacy rate2 in exile, which sits higher than the global average. Those who are not digitally savvy can still register physically or through the toll-free number. Once registered EC can issue an electronic or a physical voter ID. This will encourage more people to register, as it is convenient, eco-friendly, cost effective and time saving. Issuing voter ID will encourage higher engagement in the actual elections, as Green Books can be misplaced or lost even after registration and getting a new book issued in time is bureaucratically next to impossible. On the other hand, E-Voter IDs can be downloaded anytime. Online voting might perhaps also be explored down the line although realistically, it will be a while before this is made possible. Postal voting however can be achieved in the immediate future. Tibetans are scattered across different cities, towns, and villages in the world. Time limitations and other factors prevent many from travelling to a polling booth. There are also many people who are unable to vote due to underlying health conditions. A system of postal voting with a self-declaration can make our voting process more practical.

With the advent of digitization and mail vote, every single Tibetan can be reached. As per the SARD report, there are three Tibetans in the Czech Republic and eight in Iceland. If these individuals and smaller communities can be facilitated to vote by mail, it could mean a big step within our electoral system. In New Zealand for instance, with just one Tibetan living in Wellington the individual would have to drive eight hours to Auckland or take a flight to cast his vote at the preliminary as well as the finals. Similarly, others find themselves in the same predicament. These act as a deterrent and rightly so. As previously mentioned, we cannot conform to a singular blanket rule because the make of our society is unique.

Voting from Rest Homes or Old Aged Homes should be available as well. Almost all the Tibetan Old Aged Homes in exile come under Settlement Offices in their respective areas. Due to current climate owing to COVID-19 and various other age-related problems they are more likely to miss out. These facilities are under constant care and managers can be appointed as voting officials under clear direction and supervision. Among other things, right now, we should also enable voting from hospitals, managed isolation, quarantine facilities, or those in self-isolation and EC should have concrete plans for different Covid-19 levels of lockdown.

Early voting or advance voting can also be applied to certain places where there are permanent Settlement Offices and Office of Tibet with a population over one thousand. This can also alleviate the issue of mass gathering in sensitive times like the pandemic and social distancing protocols can be adhered to if large groups of people do not have to gather at one location on one given day to vote. Advance voting can start two weeks before the actual voting day and people can do so at their own pace and convenience. These have proven to be remarkably effective in the recent New Zealand and the United States elections.

The US Presidential election held in November 2020 had the highest voter engagement in 120 years. At least 158.8 million American people voted against 137.5 million Americans in 2016. That is a good 20 million voters more than their last Presidential election. The difference this time around was close to 102 million Americans voted early – either in person or by mail. If voting is made easier, more people will vote.

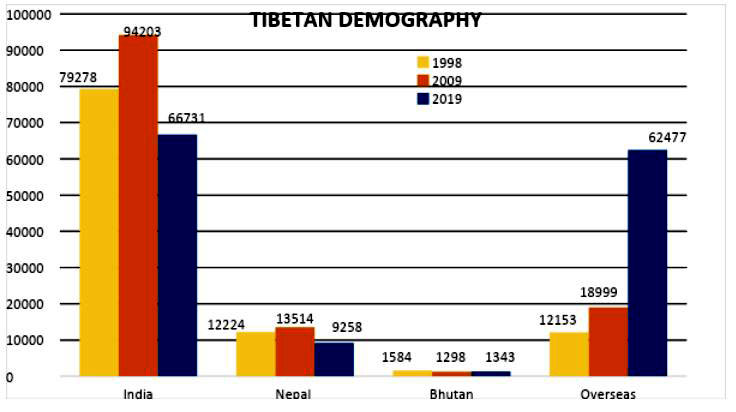

To understand how to effectively connect with Tibetans worldwide EC needs to study the diaspora closely. The latest Tibetan Demography Survey 20193 recorded 77,332 Tibetans living in India, Nepal, and Bhutan. The recently published Baseline Study of the Tibetan Diaspora Community outside South Asia by Social and Resource Development Fund (SARD) of CTA conducted a study to explore population and demography outside the three traditional exile Tibetan communities. They found that there are approximately 62,477 Tibetans living overseas with a ten to fifteen percent error margin to account for the low level of participation.

Our population at these counts stands at 139,809 approximately. The SARD report estimated the number of Tibetan children in North America between the ages of 5 and 18 to be at 4000 with approximately 36,098 Tibetans in total. Going by that logic if we account for eleven percent of the entire population in exile to be under 18 there remain a deficit of thirty six percent 44,733 4 of the eligible adult voting population that are yet to register for the upcoming election. Therefore, it is imperative that the Offices of Tibet and subsequent Tibetan community organizations and associations investigate these thirty six percent of untapped resources.

Tibetan migration overseas has forged ahead in droves. A full-fledged multi-language user-friendly website as per demography based on the needs of Tibetans all over the globe is required. With almost a 50-50 split5 in current population in the East and the West, there is a sizeable section of younger Tibetans who only read, write, and speak in foreign languages. For them to participate we need to go global just as Tibet TV has done. CTA has every resource to translate the Tibetan Election website into different languages. This way voters will be more informed and educated, encouraging higher levels of involvement. If the current trend of approximately 42,449 Tibetans migrating to the West within the last decade continues, there will only be around 35,000 Tibetans left in India, Nepal and Bhutan by 2030. With the bulk of population overseas then, the need for a change in the electoral system is now more than ever.

The Tibetan system of governance does not have a party vote, so it is simply electing one’s representative(s) in the Tibetan Parliament in Exile and President (Sikyong). Information can be consumed in various ways and right now social media is a strong medium. Again, as is in many democracies worldwide, political slander in campaigns remains popular in the Tibetan community. Voter education is important, and this can be assisted further by the Election Commission with the initial introduction of the candidates on a single platform that can serve as a one stop shop. It is the voter’s responsibility to further study their candidates. The process needs to be more robust with a proactive approach. The fact that Tibetan NGO’s, regional Tibetan associations, or any organization in exile cannot endorse or provide a platform to candidates for campaigning also limits their exposure.

Close to 500 Tibetans from India, Nepal, Bhutan, Australasia, North-South America, Europe, Africa and other parts of the world engaged in an online survey we carried out last month. Fifty percent were aged between 35-44, thirty percent between the ages of 18-34, fifteen percent between 45-54 and rest above 55. Of the predominantly eighty percent of male participants, we learned at least thirty one percent are inactive voters. That takes us in the vicinity of the thirty six percent of untapped resources who did not participate at all in our elections.

Eleven percent of survey respondents aren’t registered to vote in the upcoming elections, which is again close to EC’s count of a twelve percent decline. The major reason behind this is our rigid enrolment structure. Ten percent did not have their Green Books with them and another ten did not want to vote. Therefore, EC needs to study how to improve voter behavior and come up with an easier enrollment/voting procedure. Adding an additional five days to encourage more people to register unfortunately is not a solution.

In conclusion, sitting out is not an option. Voting needs to be a Civic Right rather than mere Civic Duty. If Tibetans can attend community concerts, movies, community picnics and parties, the least we can do is vote every five years for our country, our future, and the next generation of Tibetans. If you have ever introduced yourself as a Tibetan to anyone at all you need to ask yourself – what have I done for Tibet apart from calling myself a Tibetan.

***

* Tenzin Sangmo is a New Zealand based financial analyst and former reporter with Phayul

* Wangdue Tsering Kharlo is the President of ATA, New Zealand and former Executive Director of Active Nonviolence Education Center (ANEC), Dharamshala.

*****

Endnotes:

1. Average of registered non-voters in 2006, 2011, 2016 elections

2. Sikyong Lobsang Sangay at Cambridge Union, London 2019

3. Tibetan Demography Survey 2019

4. 139,809 less 11% less 79697 registered so far

5. Baseline Study of the Tibetan Diaspora Community outside South Asia by Social and Resource Development Fund (SARD)

****

References:

CTA Planning Commission. Demographic Survey of Tibetans in Exile – 2009, August 2010

Demographic Structure of Tibetans in Exile, Chapter III (TDS’98 & 09)

www.migrationpolicy.org/article/global-nomads-emergence-tibetan-diaspora-part-i (122,078 Tibetans worldwide) –2009 US & Canada count

www.tibet.net/about-cta/tibet-in-exile

Tibetan Demography Survey 2019 – Workforce information System, CTRC

Baseline Survey, SARD

www.polyas.com/election-glossary/voter-apathy

www.tibetoffice.com.au/planning-commission-releases-report-on-second-tibetan-demographic-survey

www.tibet.net/about-cta/tibet-in-exile