(TibetanReview.net, Jun26’20)

Apart from Tibetans, the greatest beneficiary of a Free Tibet will be India. The recent Chinese incursion and brutal murder of twenty Indian soldiers in Galwan Valley in the Ladakh region of Northern India is yet another reminder of a prophetic letter by Sardar Patel to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, dated November 7, 1950. In that letter, Sardar Patel wrote, “…There can be no doubt that during the period covered by this correspondence, the Chinese must have been concentrating on an onslaught on Tibet. The final action of the Chinese, in my judgment, is a little short of perfidy. The tragedy of it is that the Tibetans put faith in us; they choose to be guided by us, and we have been unable to get them out of the meshes of Chinese diplomacy or Chinese malevolence. … In the background of this, we have to consider what new situation now faces us as a result of the disappearance of Tibet, as we knew it, and the expansion of China almost up to our gates. Throughout history, we have seldom been worried about our north-east frontier. …We had friendly Tibet, which gave us no trouble.”

While the recent Galwan Valley incident is highly distressing, unfortunately, as long as Tibet remains under the total control of China, it’s almost certain that such an incident will happen again.

At the core of the Sino-India border conflict is the issue of Tibet. Historically, China never shared even an inch of border area with India until the 1950s when China brutally occupied Tibet. A historical analysis of authoritative historical documents by Chinese Professor Hon-Shiang Lau (20019) shows that Tibet was never a part of China before 1950. By the end of the 1950s, the Chinese occupation of Tibet was completed. The sorrow and devastation tore through a thousand years of peace; human and cultural genocide soon followed in Tibet and continues today. A semester-long class that I had with Ambassador Nirupama Rao, (former Indian foreign secretary and ambassador to China) at Columbia University reinforce my initial assessment that no matter how many rounds of the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination for India-China Border Affair (WMCC) meeting takes place or how sweet the diplomatic soundbite may be, there can never be a constructive border solution between India and China as long as Tibet is under Chinese occupation. In this article, I will discuss how the continued Chinese occupation of Tibet costs Indian tax-payers, on average, US$ 7.16 billion annually, and how this amount can be used to solve India’s other urgent developmental needs.

Before proceeding further on actual empirical analysis, I would like to share a short personal story. Like any child, my favorite activity around bedtime was to listen to exciting stories that my grandmother used to tell me. She was born and raised in Tawang (a border-town between China-occupied-Tibet and Northeast, India) around the 1920s before she married to my grandfather, who was then serving as the governor of the southernmost district of independent Tibet called Lhuntze dZong. When I was in Tibet, I was always fond of listening to my grandmother’s bedtime stories. She used to tell me how green and beautiful Tawang was. Given the fact that there was no forest around Lhasa city, where I spent my early childhood years, my grandmother’s stories of forest and greenery intrigued me. I often requested her to take me to Tawang to see the forests. She said that she couldn’t take me to Tawang as it was “closed.” To a naive mind of a child that I was, being told that the entire region was “closed” did not make any sense. I resisted and argued, asking how it was possible that she could go back and forth from Lhasa to Tawang in the ’30s and ’40s without any difficulty, and I couldn’t go now even with advanced modes of transportation.

Finally, in 2012, I was on a trip to Tawang. It was just like what my grandmother told me back then – greenery everywhere. I hired a local Taxi and went to visit Bumla, the border post between China-occupied-Tibet and India, where official border personnel meeting between the Indian Army and the Chinese Army for regular interactions are held. The distance from Tawang to Bumla is about 36 Km, and it took our taxi around 4 hours to reach there. Despite being a strategic military route, the roads are treacherous and often blocked by landslides. At Bumla, I interacted with some Indian border personnel and asked them how far Lhasa was from there. They said it was about 420 km but would take only about 8 hours by car. The fact that it only takes about 8 hours to travel about 420 Km from Bumla to Lhasa shocked me a little. The terrain at each side is about the same, if not harsher on the Tibet side, but the road was much better on the Tibet side of the border. That experience reminds me of the stories that many people I met at Tawang told me about the 1962 Sino-India war. While India already lost the 1962 war before it was even fought, inadequate road and transportation conditions further added up to India’s defeat.

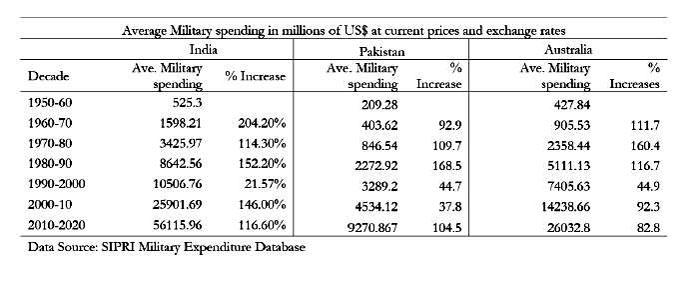

Although much has changed since the early ’60s, the continued Chinese occupation of Tibet still costs dearly to Indian tax-payers. As shown in the table below, India’s average military spending1 increased by 204.20% in the decade of 1950-70 as compared to other countries in the table. Australia and Pakistan, as an example, the increase during the same period is only 111.65% and 92.9%, respectively.

What caused this three-fold increase in annual military spending of India in the decade of 1950-70? I argue that China’s occupation of Tibet and subsequent India’s recognition of Tibet as a “region of China” through the Panchsheel Agreement of 1954 had a significant causal effect. While the observed increase in India’s military spending is a good indicator of the impact of the Chinese occupation of Tibet on India’s military spending, without more rigorous statistical analysis, we cannot attribute this increase solely to the illegal Chinese occupation of Tibet. To do so, I use an econometric identification strategy called difference-in-difference estimation to estimate the causal impact of the Chinese invasion of Tibet on India’s military spending. Difference-in-differences (DiD) is econometrics tool in quantitative research that attempts to mimic an experimental research design using observational study data by studying the differential effect of an event/policy (in this case, India recognizing Tibet as a region of China through the Panchsheel Agreement) on an ‘impacted/treatment group,’ i.e., India, versus a ‘control group,’ Australia. It calculates the effect of an event/policy on an outcome (i.e., annual military spending) by comparing the average change over time in the outcome variable for the treatment group, compared to the average change for the control group. While choosing Australia as a control group may raise a few technical questions, I choose Australia as a control group primarily because Australia did not have to share a border with China when the latter invades Tibet, as India had to. Furthermore, Australia and then independent Tibet does not share any social, cultural, or political relationship with Tibet as India does.

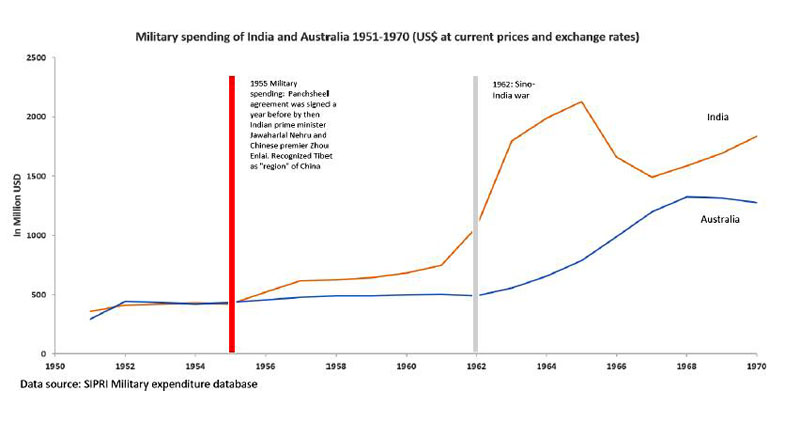

To ensure the internal validity of DiD models, the most critical assumption of DiD estimation is the parallel trend assumption. This assumption requires that in the absence of treatment, the difference between the ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ group is constant over time. The figure below shows the trend of military spending of Australia and India from 1951 to 1970. On average, Australia and India have a somewhat parallel trend on military spending from the early 1950s to 1954. But India’s military spending started increasing from 1955. Further increase in military spending was observed after 1959 when China fully occupied Tibet and the Dalai Lama had to go into exile. The sharp increase was observed in India’s military spending after the 1962 Sino-India War.

In 1954, the “Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet region of China and India,” in which the Panchsheel (Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence) was officially codified, was signed between India and China. Claude Arpi, the author of “Tibet: the Lost Frontier” wrote thus on this agreement, “Beijing got what it wanted: the omission of Demchok pass in the Treaty, (leaving the door of Aksai Chin open), the removal of the last Indian representatives and jawans from Tibet, the surrender of Indian telegraphic lines and guest houses, but first and foremost the Indian stamp of approval on their occupation of Tibet…. From an independent State, Tibet had become ‘Tibet’s Region of China’ in the new agreement.”

In estimating the causal effect of illegal Chinese occupation of Tibet on India’s military spending with a difference-in-difference estimation, I used the year 1955 as a point of variation in India’s military spending. Many historians and strategic experts agree that the year in which Nehru signed the Panchsheel treaty is the most significant event in Indo-China diplomatic relationship. The data on military expenditure over 1951-2019 is obtained from the SIPRI military expenditure database for the control group (Australia) and treatment group (India). The expense is reported in US$ at current prices and exchange rates. One potential confounder that critics might point out for an increase in India’s military spending that year might be related to continued India-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir. While it is a fact that India and Pakistan had fought earlier (1947-48) over Kashmir, there was no significant conflict between India and Pakistan in 1955 or even in the decade of 1950-60.

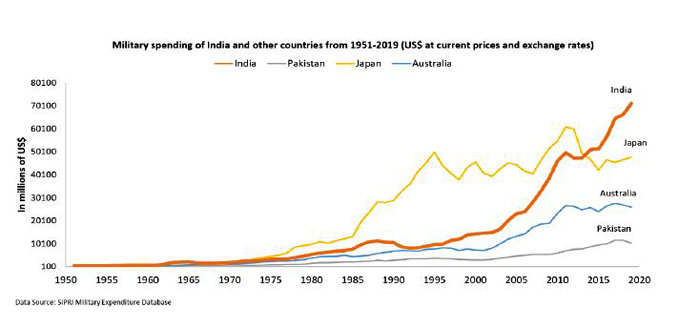

The result of the difference-in-difference estimation shows that while India’s military spending increases every year, the fact is that India now has a shared border with China due to the Chinese occupation of Tibet and the subsequent signing of the Panchsheel Agreement cost Indian tax-payer about US$ 7.16 billion annually, on average. (F (3, 134) = 30.70, p < .01, R2 = .08). This amount is a little over 10% of India’s total military spending in 2019, i.e., US$ 71.1 billion. Adding up this cost from 1955 (the year after Panchsheel Agreement) to 2019 without any adjustment to inflation and exchange rate fluctuation, for 64 years, the occupation of Tibet by China cost the Indian government US$ 462.8 billion. The figure below shows military spending in India continues to grow much higher than in many other countries. With annual military spending of US$ 71.1 billion in 2019, India today ranks third highest military spender in the world after the US and China.

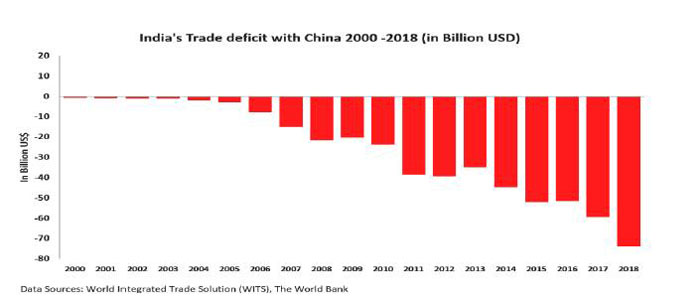

For countries like India, which according to the latest World Bank report, is a lower-middle-income nation (The World Bank, 2019), the annual amount of US$ 7.16 billion or INR 54,395.8 Crore is not small. This amount could fund one of India’s most successful welfare programs such as Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) for several years. According to the report from India’s Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), the central government of India allocated ₹16,335 crores to ICDS program in the 2018-2019 fiscal year. The annual US$ 7.16 billion that India had to spent for military purpose solely because of China’s continued occupation of Tibet could fund ICDS for about three years. Similarly, this amount can be utilized to eradicate poverty in India by investing in building the human capital of India and thus making India strong from within. Alternatively, this amount can also be used to address the ever-increasing trade imbalance between India and China, as shown below.

Less measurable but perhaps far more significant is the impact of environmental destruction and rampant damming of international rivers that originate from Tibetan plateau and its potential impact on downstream nations like India. Many experts attribute the reason for India and China having the highest population in the world to rivers that originate from the Tibetan Plateau and flows through India and China, thereby creating very fertile downstream lowland that could sustain such population growth.

The Indian government statistics in 2019 showed that 43.21 percent of the workforce in the country was employed in the agricultural section. The success of agricultural production, particularly in the northern and north-eastern part of India, very much depends on rivers that flow from the Tibetan plateau. However, because of the Chinese occupation of Tibet, these important rivers are being controlled by China, apparently without any regard to downstream countries. A 2020 study by two American climatologists shows that China appears to have directly caused the record low water levels by limiting the Mekong River’s flow. (Basist and Williams, 2020) Because of the Chinese weaponization of Tibetan rivers, agricultural production has fallen sharply in downstream nations like Thailand and Vietnam. For instance, Thailand, one of the world’s leading sugar exporters, is expected to produce up to 30 percent less sugar than in previous years due to recent drought, which was further exacerbated by China limiting the water flow of Mekong river. Similarly, in Vietnam, about 94,000 hectares of rice fields are expected to be affected because of saltwater intrusion across the Mekong river basin due to drying up of the Mekong River. If these rivers can be used as the most effective weapons, as many strategic experts believe China will, India could potentially face irreversible consequences as Chinese reckless environmental destruction continues in occupied Tibet.

While the recent Galwan Valley incident is highly distressing, unfortunately, as long as Tibet remains under the total control of China, it’s almost certain that such an incident will happen again. A 2010 confidential document for the U.S. Department of State leaked by Wikileaks indicates that infrastructure development by Chinese in Lhoka prefecture of occupied Tibet, which according to China includes Tawang, was in part to prepare a “rear base” should a border clash arise. While China appears to be economically influential at the global stage, we must understand that the Achilles heel of China lies in Chinese occupied territories like Tibet. As rightly noted by Sardar Patel in his last letter to Nehru, “Throughout history, we have seldom been worried about our north-east frontier. …We had a friendly Tibet, which gave us no trouble,” all these issues can be sorted out much quickly and even permanently if Tibet is free and Tibetans have more significant says on the Tibetan plateau. Similarly, Indian tax-payers would not need to spend an average of an additional US$ 7.16 billion annually for the country’s military purposes. Hence, it is high time for India to reconsider India’s Tibet policy and officially recognized Tibet as occupied territory. Doing so greatly benefits India’s basic national and security interests

—

1. Border Security Force, the Central Reserve Police Force, the Assam Rifles, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police and, from 2007 the Sashastra Seema Bal. Figures do not include spending on some military nuclear activities (e.g. nuclear warheads).

—